Connecting international law with art: a collab between Asser Institute x KABK

16 december 2024

Can art make international and European law more accessible to the public? An project by the Asser Institute and the KABK explores this question through the lens of photography. For three months, fourth-year

Can you tell us about yourself?

Salome: “I am a lens-based artist and writer. I like engaging in a broader practice of curating, editing, and writing - especially collaborating and facilitating interactions. I love exhibitions and (collective) bookmaking.”

Daria: “I’ve been doing photography since I was 14. I decided to make it my professional and academic pursuit because it was the only thing I imagined myself doing, and I'm glad I did. Since coming to the KABK, I have seen a lot of progress in the way I approach my projects conceptually.”

Anastasia: “Photography has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember - it’s something I fell in love with thanks to my father. Some of my earliest memories are tied to photography: my first steps were captured on Polaroid by my father, and he gave me my first Photoshop lesson. However, pursuing art as a career didn’t feel feasible in a time of political and economic instability in my country. So I chose what seemed like a ‘stable’ path and earned a law degree. I worked in various legal roles for six years, but eventually, I decided to return to my passion for photography and art.”

Why do you want to connect international law and art?

Anastasia: “I find art and international law to be not as far apart as one might think. Both are rather removed from the average everyday life, yet they place humanity at their core, as the primary value and motivation for development. International law, like art, is not omnipotent but undoubtedly essential. Like the researchers at the Asser Institute, I question the current state of affairs.”

Daria: “My desire to connect international law and art stems from the graduation project I am working on. That project is about the biggest tragedy in Romania’s recent history, a club fire caused by a fireworks accident which killed 65 people. The layers of corruption and incompetence behind it drew me to this collaboration with the Asser Institute. I think art can be a great facilitator for the translation of law into something everyone can relate to in order to make it more transparent.”

Salome: “I was drawn to this project because of the Asser Institute's work on the public interest - a buzzword that is so hard to define! An artistic collaboration like this could provide some tangibility to that concept. I like stepping into spheres that are unknown to me and especially to a larger public, in order to make them more accessible. My work is all about facilitating conversations.”

What is your project at the Asser Institute about?

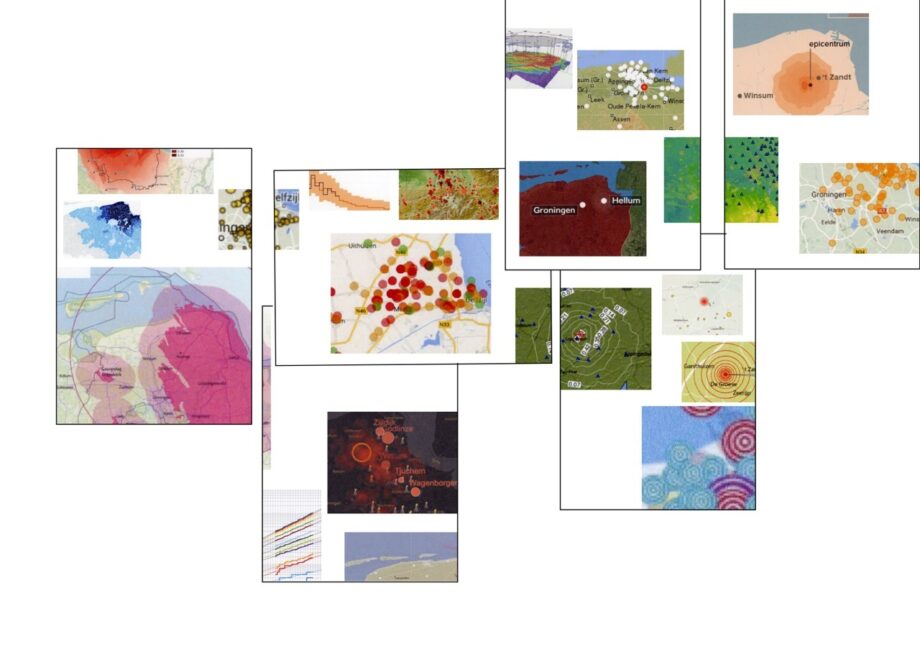

Salome: “I opted to investigate the very timely case-study of the investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) arbitration between ExxonMobil v. the Kingdom of the Netherlands. For decades, the people of Groningen suffered from earthquakes induced by gas fields. Now that the state finally acted upon it, the fossil fuel company sued the Dutch state in October 2024 for compensation in response to the closure of the gas fields. The arbitration will be held in Washington, with the date to be announced. These seemingly distant arbitrations do affect people in the Netherlands. Therefore, I want to explain to a general audience what is actually going on.”

Daria: “My project stems from my interest in the buildings that represent international law, which are so present in The Hague. As I read more about how the architecture of these courts and tribunals can communicate, I stumbled upon an article by Renske Vos and Sofia Stolk (Asser Institute research fellow) called: ‘Law in concrete: institutional architecture in Brussels and The Hague’. In the piece, the authors wrote about: ‘…concrete materiality as that which makes international law tangible for its audience and constituency,’ which made me want to photograph this tangibility and assess how easy (or difficult) it is for the public to gain access to these international legal institutions.”

Anastasia: “I am exploring the use of consumer drones in modern warfare. I believe this subject represents a crucial intersection where art and international law can complement each other. To me, a drone has always been a simple camera. However, after almost three years of the ongoing war in Europe, I see drones being used in a troubling way - as tools for remote-controlled killing. While this adaptation of the camera has existed for some time, it has never felt as apparent as it does now. This is why I am so interested in this topic, especially because it currently operates beyond the control of international law. I aim to bridge the gap between the dual use of drones, the imagery they produce, and the reality they depict.”

Can you give us a sneak peek into your creative process?

Anastasia: “I think working on a photographic project is quite similar to working on a research paper, especially for a project like this. I spend a lot of time reading, discussing topics that interest me, and gathering insights: sometimes I get hyper-focused and end up talking about drones with my mom or even during a date (laughs). I also share my process to get feedback, I watch online footage and artworks for inspiration, and I ultimately create my own photographs and writings.”

Daria: “For me, research is the motor of my recent projects. It inspires me with ideas of what I could do. The article by Renske Vos and Sofia Stolk gave me information about the International Criminal Court (ICC) building in order to approach it. However, even after I start taking photographs, I continue doing research and try to implement it in my project along the way.”

Salome: “The creative process is a lot of trial-and-error, but it is mostly in conversations with people that I figure out how to proceed. When I start talking and presenting, my brain starts to make sense of things. Usually, I don’t have these cliché ‘artist’s revelations’ in which I suddenly have this amazing idea to work with. But at a certain point, it will all slowly start making sense, and I can articulate what my work is about - and gladly, that already happened for this project! This usually comes with a lot of excitement, because I know that then the production truly starts.”

What has been the most challenging aspect of this project so far?

Anastasia: “It has been a long time since I graduated from the law department, and I am not used to reading such dense legal texts anymore. Honestly, I think that lawyers would benefit from adding a touch of poetry to their writing!”

Daria: “It was a bit challenging in the beginning, especially during my first research strand meeting. I am not a lawyer or a researcher, so I felt like an imposter. Yet, I was happily surprised to see how everyone included us and seemed interested in what we are working on.”

Salome: “For sure the terminology. ECT, ISDS, ICSID (International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes), ECS (Energy Charter Secretariat) - it felt like I was drowning in a soup of abbreviations….. Also: what on earth is an arbitration center?! Why do people, or companies rather, not go to a national court? It is these findings that I want to share with an audience, to provide some sense of how this abstract landscape of ISDS can affect everyone.”

What can visitors expect at the final exhibition next year?

Anastasia: “I hope that visitors will embark on a thought-provoking experience, towards a new way of seeing contemporary weaponry and warfare. My goal is to guide them along a path of reflection, challenging the familiar imagery and inviting them to question how these technologies are used. Especially as warfare becomes both more deadly and more ‘playful’ for viewers who safely spectate the war from home.”

Daria: “The visitors to our exhibition will see a demystified impression of the institutions that represent international law. I hope that my images will spark conversations and trigger a critical perspective on the architecture of international law.”

Salome: “I want to send the audience on a quest to 'find the public interest'. Spoiler: the public interest in the case of the current arbitration between ExxonMobile and the Dutch state is hard to find! The audience will enter a space devoid of humans, and face found footage of highly polished facades of arbitration venues, and of the company and the state involved in this arbitration. I want to create a space for participation and exchange, while conveying information about the case and the larger legal framework of ISDS. I think that many people simply have no idea about these mechanisms of international law. My work also speaks of larger issues – power imbalances and the constitution of the public interest, for example. In that sense, I hope that my installation will

trigger some thinking about the relation of oneself to the public interest and larger institutions. What is the public interest? And who needs to act upon the public interest?”

In 2025, the students’ work will be on view in an exhibition in The Hague, accompanied by narratives that connect their art to legal realities. Following the exhibition, the collection will be displayed at the Asser Institute, to continue the conversation on international law’s human impact.

About the Artist in residency programme

The Artist in residency project, co-organised by the Asser Institute and the Royal Academy of Art The Hague (KABK) draws inspiration from the Asser Institute’s research agenda, ‘Rethinking public interests in International and European Law - Pairing critical reflection with perspectives for action’. The residency seeks to visually communicate the effects of international and European law on citizens and professionals, with the aim of creating a greater understanding and engagement.