We are happy to announce that from many compelling proposals submitted to an open call for the Design and the Deep Future Research Group 2022-23, the following have been selected: Louis Braddock Clarke (tutor, Hacklab and Geomedia, BA Graphic Design), Alexander Cromer (IST Study Coach, BA Graphic Design), Rana Ghavami (tutor, MA Industrial Design and Objects in Relation IST), Carl Johan Högberg (tutor, BA Fine Arts) and Victoria Meniakina (tutor, Interior Architecture and Furniture Design). We are also pleased to welcome Benjamin Earl (tutor, BA Graphic Design) as Designer-Researcher in Residence.

The proposals were reviewed by Alice Twemlow, Rosa te Velde and Martha Jager.

Overview of the participants and their research projects:

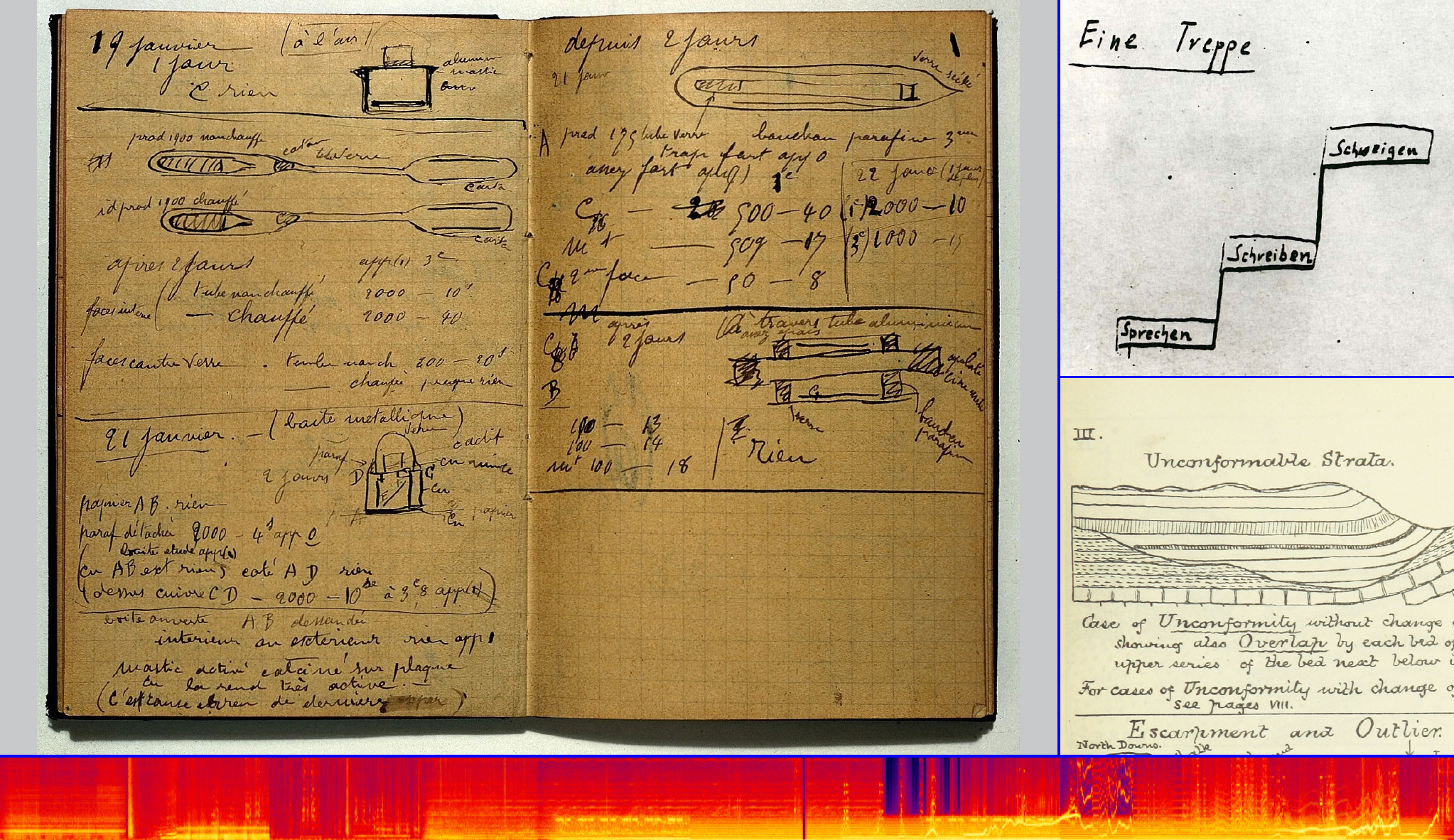

Weather Gardens: Active Listening to Drifting Geographies

How can plural acts of listening trigger imaginary climate narratives through field research?

Keywords: Listening, Climate Imaginaries, Sampling, Witnessing, Indigenous Knowledge, Geological Acceleration, Weather, Telluric Currents, Amplifying, Translating, Walking & Talking, Non-human Agency, Climate Intimacy, Spectral Thinking.

Weather Gardens is a proposed method, discourse, and space for the act of listening at sites of geological disturbances. The project focuses on hearing as a practice to pluralise and amplify the sonic signatures of ecologies, to further open up potentials for climate imaginaries. Listening to the landscape as a whole (people, materials, animals), and through varying magnitudes, allows for research that steps away from being fixed and into an active mode of telluric-drifting. How can sound create intimacy with the Earth as it goes through rapid shifts due to the climate emergency? What are the new sonic signatures of the Anthropocene?

The act of listening will be a focus point of the research period; asking questions, generating sonic imaginaries, and drawing cosmograms about the unheard ecologies will become transmissions of our ever-shifting Earth. Through a method of hearing I will explore the oral linguistics of the Anthropocene, investigating the relationship between physical materials, and their immaterial emissions; rocks and language, water and myths, ice and rumors.

The ongoing research is rooted in fieldwork; going to a site, amplifying the unheard, starting a conversation. The sites of research I will consider as gardens, flourishing with multi-species, dancing minerals, and rumbling noises. At these sites an exploration of entanglement between landscape shape and landscape sound will be inquired – How does a volcanic mountain influence underground sonic utterances? How does a meandering river shape local language? Do spoken words change to the beat of melting ice?

Voicing Unverifiable Realities Beyond the Archive: Ecological Crisis and the African Diaspora

How can voice help us to imagine the unverifiable realities that exist outside of the archive? And further, how can such a practice contribute to alternate means of historicizing and analyzing the ongoing realities of ecological crisis within the African Diaspora?

Keywords: Voice, Storytelling, Spoken word, Black Ecology, Care, Ancestral Communication, Poetry, Critical Fabulation

I’d like to spend my time within the research group investigating the archive in order to make visible the invisible histories of the archive, place them into the imaginary as a means of resistance against the violence of colonial imagination. Additionally, as a spoken word artist, matters of voice are essential to my research and artistic practice. My research addresses care, voice, ancestry, and ecology in relation to the trans-Atlantic slave trade and investigates how spoken word performance art can provide a means of disrupting violent processes of colonialism and toxic environmental stewardship. But, with increasing urgency, this word invisibility reveals itself to me as a keyword and topic of study.

In her article 'Venus in Two Acts', Saidya Hartman writes: 'The irreparable violence of the Atlantic slave trade resides precisely in all the stories that we cannot know and that will never be recovered'. I believe that imagining and telling these stories can help Black communities within the African Diaspora to re-define our current, and intimate, nature-culture relations which were defined and shaped by colonialist fabulations and methodologies.

The primary site of research begins and ends with my body directly through my artistic practice, but also involves delving into the archives (The Black Archives, family archives, municipal archives, etc), collecting stories and storytelling methods from the Arctic, the Sahara, and elsewhere (the extreme environments which are also being affected by climate change in irreparable ways).

Ethics in Methods: Aesthetics, Sense-making and the Ongoingness of Colonial Histories

How is dispossession, displacement and the severing of the relational ties between people, labour and lands not only investigated, exposed, storied, and visualised, but also, how is it historicised in design education in relation to the ongoingness of colonial and imperial histories? What are the ethical implications of the ways in which methods are taught in design education? How do practices of (re)presentation carry ethical meanings, and how are they embedded in decolonial aesthesis and aesthetics as sense-making?

Keywords: Material as Witness, Tracing as Method, Story-Telling, Practices of (Re)Presentation, Embodied Knowledge, Aesthetics as Sensing and Sense-Making, Ethics, Methods, Decolonial Aesthesis, Critical Design Pedagogies.

There are vastly different stories that one can trace along and across an object; the details that make an object particular, the ways of life that enable one to come across an object, the strong associations we have with an object, how an object perpetuates and serves a propaganda, how an object has traveled historically, or the bodies, materials and relations that are involved in making an object, including human bodies.

Prompted by the erasures and displacements of people, labour and lands who are affected by design practices and (hi)stories, ‘tracing of materials and things’ has endured as an active method of uncovering and questioning how materials and things are excavated, produced and destroyed, for whom, and at what costs—in turn exposing how design cultures reproduce underlying power structures by severing people, labour and materials from their life-worlds.

Recent research projects in the Netherlands that have grappled with such issues include Lithium, an exhibition that reflected on the role of this chemical element in powering today’s economy at Het Nieuwe Instituut in 2020, along with their broader research trajectory Matter, which inquires into how contemporary practices are embedded in various techno-political systems, and how designers can challenge the market-driven approaches to materials, and promote alternative value systems. Initiatives of the Research Center for Material Culture (RCMC) in this regard include the 2017 seminar series Global Earth Matters, in which they engaged the materiality of objects by opening broader questions on labour and making, skills and craftsmanship, and issues surrounding the (exploitative) economies of which the objects are part. Such excavations and historical exposures have laid the groundwork for questioning how the global effects of local activities are made tangible and thus legible in and through design and material cultures. It is in line with these research trajectories, discourses and practices that I see parallels with the Design and the Deep Future project, which seeks a more nuanced understanding of climate justice, planetary degradation and the loss of biodiversity.

What happens when aesthetics, making practice, social relations and local life are brought together through geographical expansion and the cataloguing of ‘other’ ways of knowing, imagining and being in the world, as ‘new paradigms’ for methods, aesthetics, and thematics in design? Such ways of presenting and drawing upon ‘other’ ways of knowing and imagining design through other worlds side-steps and in fact obfuscates

the embeddedness of design in unjust labour conditions, exploitative economies and their detrimental effects on the climate. It suggests that one can maintain the traditions, references, methods and readings inherent to design merely through expanding and supplementing its view and scope.

In line with the work of design studies scholar Ahmed Ansari, I ask how can we deal with the ways in which ‘other’ knowledges are subjected to ontological flattening, as designers and curators translate these encounters and archives into terms that are palatable to Anglo-European knowledge systems in design education. What are the potential risks, limitations of expanding and reconfiguring histories in such ways? What are the ethical implications of understanding life-making practices embedded in postcolonial histories as a new paradigm for methods, aesthetics, thematics in design education? How are these ethical implications dealt with in our teachings?

Madder: We Are All Pigments

What would a student-driven, academy-wide, speculative pigment research laboratory look like? Could pigments act as agents and carriers for environmental storytelling, for the critical, for the poetic?

Keywords: Madder; Matter; Decoloniality; Dyestuffs; Storytelling; Toxicology; SF; Earthlessness

Madder lake is a fermented pigment derived from boiling the roots of the common Rubia tinctorum, beloved since antiquity for its ruby red hue. The Dutch madder lake was once manufactured around Zeeland, premier on the continent for its hue but fleeting, needing multiple layers to counteract its transparent nature. Vermilion red, on the other hand, was sought for its brilliant opaqueness, but toxic and deadly. Both are now all but vanished from use, save for novelty uses, finding themselves replaced by synthetic pigments based on petrochemicals and distillates, similar to nearly all commercial pigments and dyes. The utilisation of synthetic pigments and dyestuffs is ubiquitous; they are cheap, color-fast, reliable, and produce a wide range of bright hues impossible to extract in large amounts from natural sources. Compared to many natural pigments and dyes, such as lead, cinnabar, various sulphuric yellows, synthetic similes are nontoxic and safe to use. But is that really true? And safe for whom?

We are all pigments. We all use pigments, or purchase the results of their vivid impact, in art making, design production, textile dyeing, cosmetics, or reprographics. But what is often blissfully overlooked is how dangerous the production of synthetic dyestuffs really is, and how severe its impact is on the environment. It is a gigantic industry catering to a gargantuan market. Unsurprisingly, Europe incentivises the building of those factories as far away from European waterways, marine life, soil productivity and workers as possible. But if both synthetic and natural pigments are alike in their toxicity, then what do we do? In such a scenario where we feel we are 'damned if we do, damned if we don’t', passivity and apathy often take root.

My proposal to the The Design and The Deep Future Research Group is to explore how art and design academies can (and should) provide a soil for nurturing remedies to this passivity, to address and engage with these urgent and adverse impacts on all forms of life. Here, I want to argue that storytelling and speculation can act as kin-makers, as active agents of change.

We should ask the pigments to lead us. Narayan Khandekar, director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard University, poses that 'every pigment has a story'. Mummy brown—a rich brownish hue somewhere between raw and burnt umber—was favoured and revered by the Pre-Raphaelites. Aptly named, it was manufactured by grinding down mummified human and feline remains and mixing the

yield with a combination of resin or pitch and myrrh. The absolute disregard to anything other than the 'power and pride to consuming the life of others', to speak with Rolando Vázquez, reaches a fever-pitch irony in Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People—a symbol of freedom for the suppressed—is said to have areas painted with the literal

subjects of the colonised. Perhaps it is with Vázquez and thinking with decoloniality that we can start to unravel the entanglement of toxic contemporary pigment manufacturing and the modern project’s fantasy of earthlessness. If we look beneath the cracked surfaces of veneer and lacquers, we will find stories of violence, racism, patriarchy and the consumption of all Earth-beings. Colours, 'stained with red', as the artist and researcher Luisa Prado de O. Martins puts it.

Our relationship to plants and botanical materials is tightly bound to structures of power, domination and exploitation, and thus, our relationship to pigments cannot be separated from colonial violence. One could say these colours are born from it. I propose that we makers are responsible to start painting a new, messy non-linear picture. We need new metaphors, and new colours, and perhaps the place to start is right in our own backyard, nurturing young plants with crimson roots.

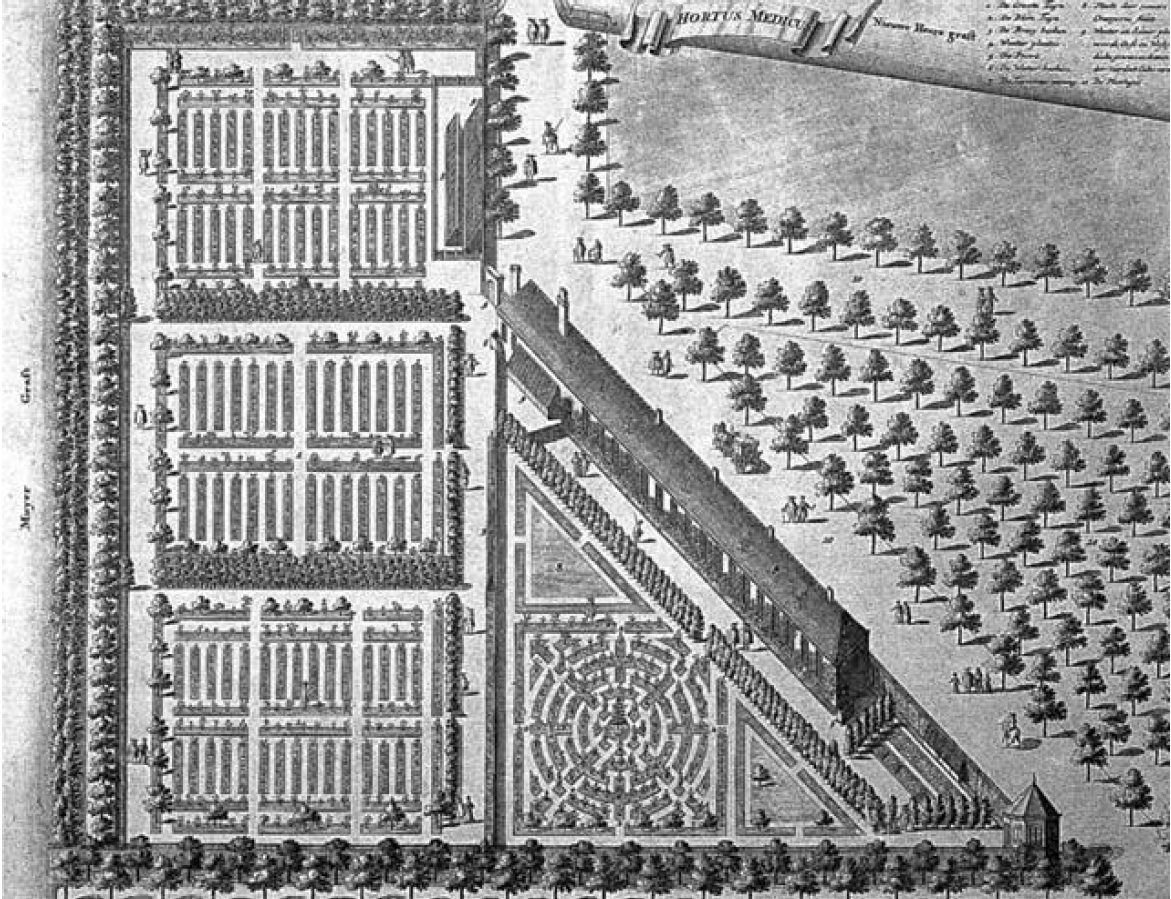

Situating the Postnatural: Material (An)archaeologies and Displaced Bodies

What is the role of design in containing, altering and controlling nature as a part of the colonial project? How botanical gardens facilitate the exploitative and extractive culture of design, displacements of species and act as laboratories containing material histories and stories across different scales and temporalities? What is the notion of natural, artificial, synthetic, native and exotic in the postnatural context? How can we create new ways of understanding matter, relate to and with non-human beings, and build ecological awareness by listening to the garden?

Keywords: Natureculture, Postnatural, (Dark) Ecologies, Toxicity and Contamination, Multispecies, Postcolonialism, Ecofeminism, Intersectionality, Practices of Care

My research is closely connected to the themes of Design and the Deep Future. As a researcher and a (former) designer I look critically at the exploitative and extractive culture of design and how it is intertwined with (geo)political, cultural, economic, and social developments. In my research, I explore the nature-culture axis or natureculture (Haraway, 2003) that design has been facilitating and perpetuating, especially in the context of the postnatural world — i.e. the current epoch of Anthropocene; or, as proposed by Haraway (2016), Capitalocene or Chthulucene. I am interested in material histories, stories and (an)archaeologies, questioning what is natural, artificial, synthetic, and the way materials ‘compose’ (Latour, 2010) and ‘compost’ (Haraway, 2016) in and around our bodies.

It is hard to deny that the way matter accumulates in the environment and inside human and non-human bodies is by design. Human and non-human bodies are also good keepers and spreaders of toxicity and contamination, (genetic) information as well as stories, histories and trauma. What fascinates me in this research is unfolding and uncovering the mechanisms of these designs through cross-temporal journeys of materials and non-human beings. Often they are perceived as ‘natural’ but are actually rather of a human design that evolved through various culturally, politically and economically influenced and accelerated alterations, displacements and (genetic) mutations.

Stories that are being told through non-human beings such as plants are for example through the Gingko Biloba could be described as a 'living fossil' – a botanical oddity, a single species with no close living relatives. It belongs to Ginkgoales, a powerful medicinal species, it carries one of the most complex DNA chains and is a real survivor – in Hiroshima, Japan, Gingko Biloba trees thrive in the post-nuclear landscapes thus becoming unique ‘carriers’ of the history of the planet in their own temporality with cultural conditions embedded in their DNA. Or take a Matsutake mushroom: 'Matsutake’s willingness to emerge in blasted landscapes allows us to explore the ruin that has become our collective home' (Tsing, 2015). Additionally, Silphium was a wildly popular plant of ancient Rome used as a condiment, as medicine and in perfumery. Interestingly, it might be one of the first plants that became extinct due to changes in the climate created by urban growth back in the ancient Roman Empire and accompanying deforestation that changed the local microclimate where Silphium grew and it has been impossible to cultivate since.

One of the best places for this research is botanical gardens, which I see as laboratories composed of different temporalities, human- and non-human creatures, living things and ‘(hyper-)objects’, like class or climate, in an entangled, multi-layered manner and across times, spaces and scales.

Coding-In-Situ

Mapping a Research Network: Tools, Places, Conversations, and Digital Community Infrastructure in the Design and the Deep Future Research Group

In what ways can the writing of code and programming be used to construct a sense of place in a digital space?

Keywords: Intimacy, Software, Network, Place, Code, Infrastructure

Central to my design and research practice is the challenge of how a website, accessible anywhere in the world, can also reflect a locality. How can digital space be imbued with a sense of place? And how can we create viable alternatives to the current centralised modes of being online?

In my work with radio (Mushroom Radio at the KABK and Good Times Bad Times in Rotterdam) I have witnessed how a publishing tool and digital infrastructure can simultaneously become a community building device that entangles itself with the activities of a local space. A device that allows people engaged with that space to broadcast their actions, it also becomes a tool to record that same activity and archive it. In this regard, the radio becomes a digital space that is highly contextual and place-full. Whilst it may not be able to visually present an overview of what that physical place looks like, the life that goes on there is translated into its programme, its web design, its jingle and its archive. This infrastructure also seems to open up a space of care that fosters autonomy as well as interdependence. In this space maintenance, organisation, and administration are just as important as hosting shows and producing events and programmes.

In my role as Designer-Researcher in Residence in the Design Lectorate, I propose to design, iterate and maintain a small, local, place-full digital community infrastructure within the Research Group. Through conversations and the testing of tool prototypes, I want to understand, and then map, the relationships between researchers, groups, equipment, protocols, students, routines and schedules, and archives within various networks in and beyond KABK.

I would like to develop a digital space in which ideas and work can be documented, resources can be shared in the forms of libraries and databases, and connections can be formed between projects and practices. As part of this work, I will use free, open-source hardware and software as I see the most potential in these tools to reveal underlying processes as well as making code accessible for others to use. Simultaneously, I will be prioritising lightweight, handmade, D.I.Y, and self-hosted development methods. I find that these methods provide a sensitivity to small-scale, intimate, and relational digital spaces. I am also interested in the ways in which these practices co-construct the uses of a digital space.

Tutor-researchers selected for the group work not only on their individual projects (guided along through group discussion, studio visits, feedback from students and other invited critics) but also collaboratively, as a group, on a range of initiatives and interventions that address the central theme of the Design Lectorate — making, teaching and researching in the context of climate catastrophe, planetary degradation and the loss of biodiversity.

The collective aspects of the group will include creating a lexicon of key terms (visual and text), collating an open-source library of references and resources, nurturing an international network of allied researchers and making and sharing essays (text, audio, visual and video). We are also concerned with developing and explicating new methods for researching this topic and for embedding it in education at KABK. The Group’s work will culminate in a conference, publication, online platform and exhibition at the end of the year.

Each year tutors in all departments (both in Design and in Fine Arts) are invited to apply to the Research Group, provided that they will be employed as a tutor at the KABK for the full duration of the Group. Tutors selected for the Group attend at least 10 all-day gatherings and use the time between sessions to further develop their projects.