Content type: Essay

Credits: Anne-Florence Neveu (MA student in Media technology, Leiden University, 2018-2020)

Year: 2019

Introduction:

In this essay, Anne-Florence Neveu uses the object itinerary method to examine the importance and poetics of seemingly inconsequential waste materials on the moon.

‘Following the trajectory of the York mesh, we see an object manufactured, tested, used and then discarded.’

As highly mediated and orchestrated events, moon landings are mythologically hued. Most things left on the moon's surface are done so purposefully and knowingly as symbols of the achievements of humanity. Alongside these celebratory and symbolic objects are more mundane items, left unthinkingly, but which attest to the more complex reality of the moon landings. This text aims to show how entwined we are with the material world, even in outer space.

To follow what I call the poetics of the insignificant, I traced back the itinerary of the material York mesh. This is a variety of tightly woven metal mesh which exists in different sizes. It is a category rather than an object and exists without a clear-cut purpose. Ubiquitous in the engineering and chemistry industries, it is used as a filtering and fencing material.

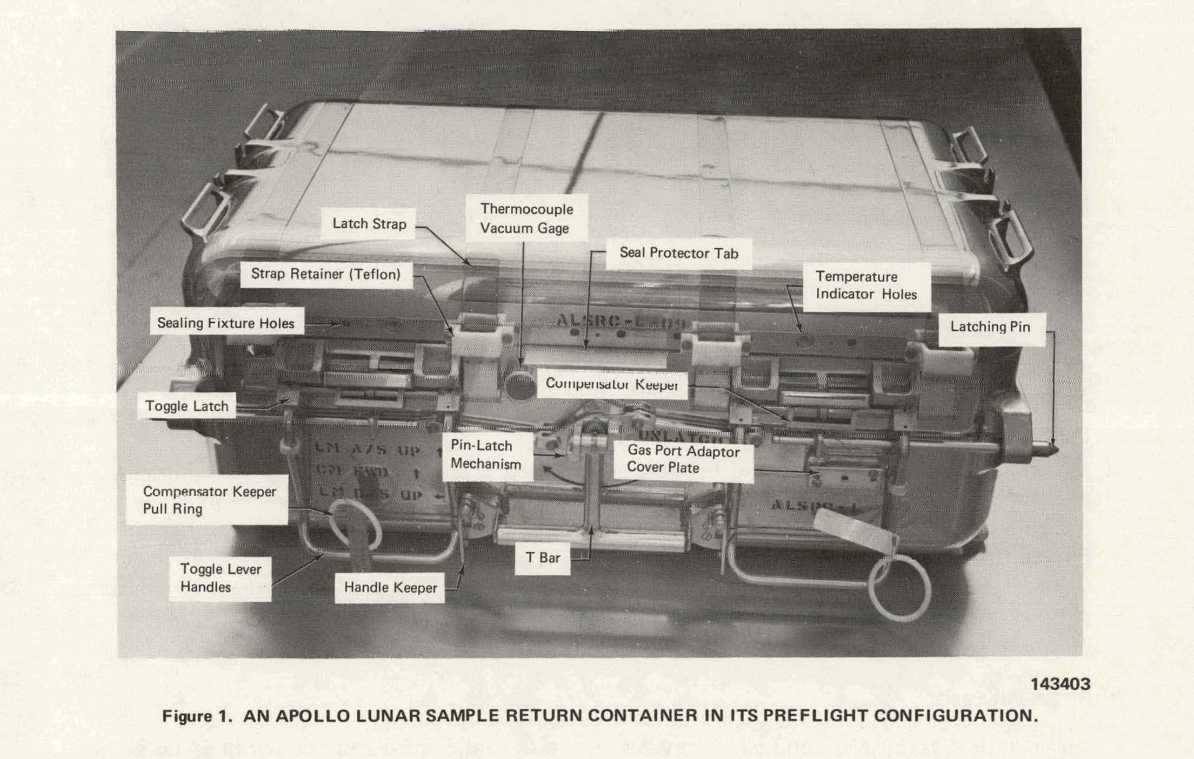

York mesh was present on Apollo Missions 11 (1969), 12 (1969), 14 (1971) and 15 (1971). It was used as padding material in the Apollo Lunar Sample Return Container (ALSRC for short, or ‘rock box’ colloquially)—an aluminium box with a triple seal designed with ‘a lunar-like vacuum around the samples to protect them from the shock environment of the return flight to earth.’

York Mesh has been found at each of the successive missions’ different landing sites

It is likely that some of the mesh returned, as planned, to Earth; however, some of the York mesh from the various ALSRCs were discarded by the aforementioned Apollo missions and left on the moon. York mesh has been found at each of the successive missions’ different landing sites: Mare Tranquillitatis,

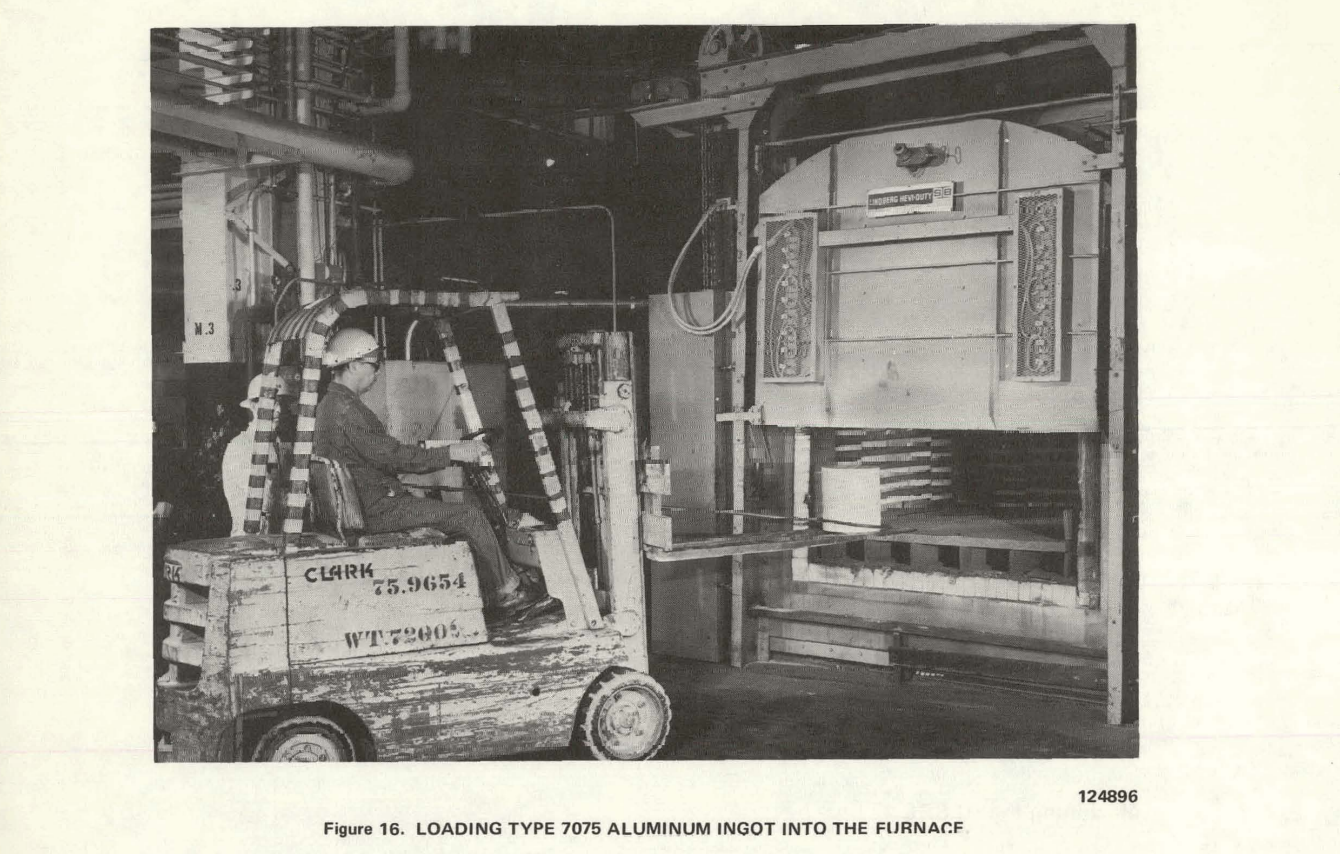

The piece of York mesh used by the Apollo 11 Mission and that was left at Tranquillity base was manufactured by Union Carbide, Nuclear Division, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

At the end of the simulation period, the mesh and the lunar sample box were sent to the Kennedy Space Centre (Florida), where the York mesh was sealed inside of the lunar sample box in a lunar-like vacuum to avoid damage that may be caused due to the change of pressure when opened on the moon.

As a part of the pre-launch milestones,

By following the trajectory of the York mesh, we see an object manufactured, tested and used with a great deal of foresight and care, and then summarily discarded. It is an object which only exists as a part of a bigger apparatus. While the mesh was a component of the ALSRC, it was not integral and was created distinctly from it. When its period of usefulness was over, it was quickly cast off. The piece of York mesh left at Tranquility Base in 1969, therefore, is a poetic metaphor for how even though objects may have gone through rigorous testing, travelled vast distances and existed in various systems of use, they often end up in our hands for only a fleeting moment before we unthinkingly part with them.