Project Title: Moon Mission 2030

Content type: Interview and graphic design

Credits: Jorick de Quaasteniet (designer and alumnus of Graphic Design BA, KABK, 2016) in collaboration with Arnout Schaap. Interview by Lara Chapman

Year: 2017–2030

‘Our mission in its essence is quite simple; we want to clean up a plastic bag. The fact that this plastic bag is located on the moon makes things more complicated.’

Introduction:

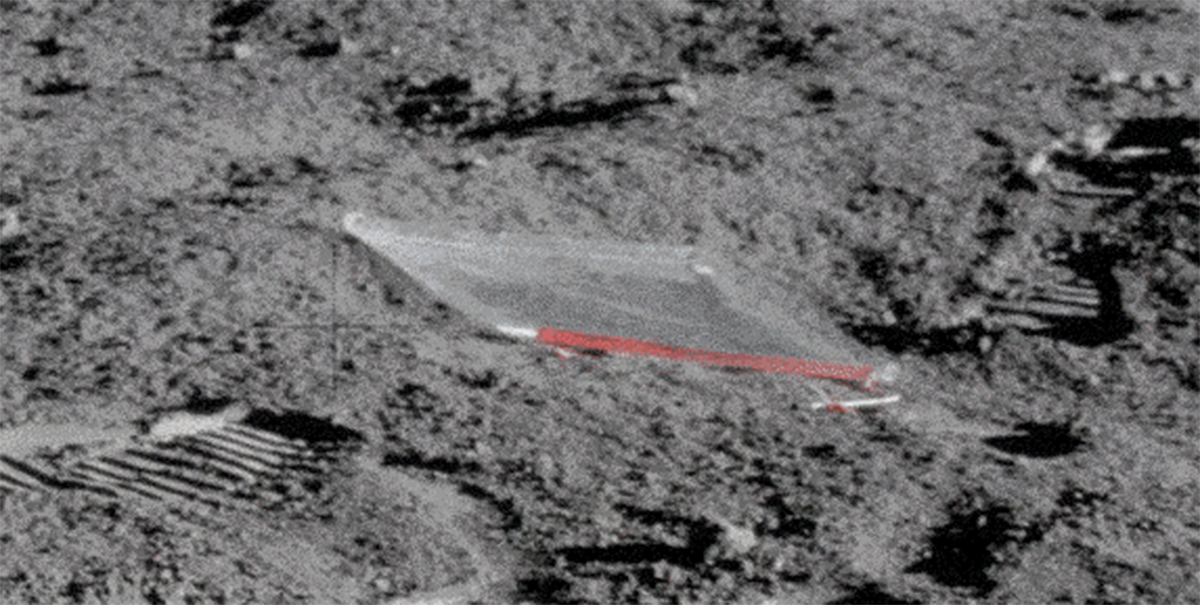

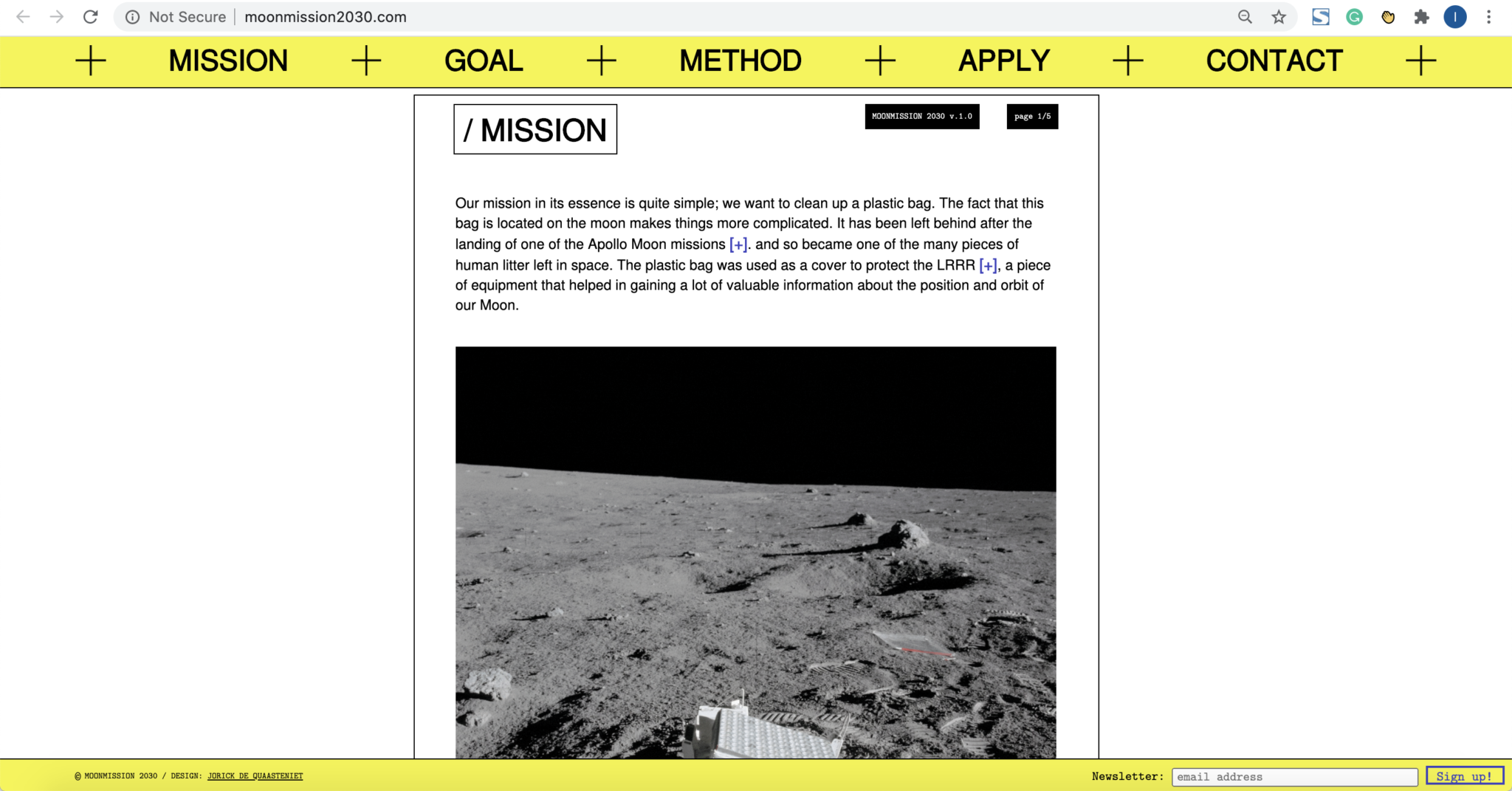

Soon after Jorick de Quaasteniet graduated from KABK in 2016 he and his friend, Arnout Schaap, were watching a documentary about the Apollo 11 moon landing. The documentary showed a photograph of a mirror that had been put on the moon’s surface so that NASA could calculate the distance between it and the earth. However, de Quaasteniet and Schaap were not looking at the mirror, instead, they had noticed a plastic bag in the background of the photograph, lying on the surface of the moon, seemingly discarded. After some research, they found that the bag was left behind after the landing of the Apollo 11 mission (the one that put the first humans on the Moon) and so became one of the first pieces of human litter in outer space. This was the starting point Moon Mission 2030, a long-term design project that aims to use graphic design and bottom-up collaborative working methods to remove that bag from the moon.

In the following interview, de Quaasteniet discusses starting a movement from nothing through graphic design and how exhibition-making and education programmes have allowed the mission to grow and mutate in interesting and unexpected directions.

Lara Chapman: Your project Moon Mission 2030 aims to retrieve a plastic bag from the moon. Why do you think it’s important to retrieve it?

Jorick de Quaasteniet: We were fascinated by the idea that they took plastic to the moon and just left it there. There is even an audio sample from this moment where they say something like ‘okay, we took off the cover and we are leaving it here’. This replicates the way we consume single-use plastics on earth, where they are discarded without any regard.

We thought it might be a good idea to pick up this plastic because it is the perfect metaphor for what we need to do on earth and the effort that it will take. The insane idea of a mission to the moon to pick up one small plastic bag can spark people’s imagination and help them to think ‘if they are going to the moon to pick up plastic, maybe we should be doing that here also’.

We thought it might be a good idea to pick up this plastic because it is the perfect metaphor for what we need to do on earth and the effort that it will take

LC: You have shown Moon Mission 2030 in various exhibitions and run workshops in schools. How do people understand and engage with the metaphor?

JQ: When we show the project, we usually get two types of reactions. The first is: ‘Why would you do that? It takes so much energy, time, effort and money just to pick up a single plastic bag and the energy used going to the moon will be greater than what you will accomplish.’

Usually, we respond to these comments by saying that we plan on hitchhiking on missions already going to the moon—perhaps we can get a small space in one of the rockets for the bag or maybe we can ask an astronaut to pick it up for us. At the moment, we haven’t set a final goal of how to achieve the mission yet as long as we can achieve it.

The second type of reaction is from people who are super excited and know exactly why we are doing it and understand the symbolism of it. It is always fun to talk to people about the why and also the if of whether we should do it or not.

Another reaction we’ve had was from somebody from the European Space Agency who said ‘you should leave the bag there because the weight of it means that it cost a lot of money to get it there and it could be recycled and used as a resource in the future as there isn’t any plastic on the moon.’ We also really like this idea that maybe we shouldn’t even bring it back to the earth but make something new from it.

It started with pure graphic design and from there everything we put out to the public, we got more input back

LC: How has your background in graphic design contributed to shaping the project and engaging the public with your mission?

JQ: When the project started it was essentially just an idea. We didn’t have any objects or content to present so we had to figure out how to get the idea across to people. The first things we developed were a logo, a mission patch, postcards and folders—very standard graphic design things—and these were what we initially exhibited. From there we were able to sit down with people and start the first educational program and eventually we could develop the embodiment of the project itself. Basically, it started with pure graphic design and we got more input back from everything we put out to the public.

LC: The graphic design seems to appropriate the visual language of the space race and is quite retro. There is a kind of paradox in using an old aesthetic to look forward. What was the thinking behind this?

JQ: That’s a good observation, I think. We started with the question of how we were going to get people interested in our project. We thought that the most interested people would be people who are really into space travel and the first space race of the 60s and 70s and so we wanted to capitalise on this nostalgia.

LC: Nostalgia runs through the project on another, more conceptual level. There was a time when picking up a single plastic bag could have been a solution to the huge plastic waste problems we are now facing. Now, the impossibility of the task on earth creates a kind of nostalgia for this moment where maybe we could have intervened but didn’t know enough or care enough to do so...

JQ: Yes, and we can still do something on the moon. In the near future, if we colonise the moon, there is a new opportunity to see how we can develop a society there that can deal with the issues that we are having trouble dealing with on earth.

LC: On your website, you ask for people to join your mission and earlier you mentioned that conversations with others have been a big part of the process. Why have you chosen to take such a collaborative approach?

JQ: Initially, we took this collaborative, bottom-up approach because my colleague and I have no idea about space and technology. We figured that, in order to achieve something, we needed to work with people with more technological backgrounds. We also thought that with just the two of us it would be very challenging and we’d need as many people, as excited as possible, to be involved.

This project has been the start of other projects because we met people who have similar ideas and are also interested in this mixture of environmentalism and space. Meeting all these people, we began to think the project was growing into something more so we started a foundation called Intergalactic Environmentalists. From there, we are working on several other projects and organising exhibitions which are composed of projects which are space-related, environmentally-related or both.

LC: How did you come up with the name Intergalactic Environmentalists?

JQ: It started as a joke when we were trying to think what our role was in Moon Mission 2030. We thought we were kind of an environmental group but that we were also going into space so we figured we were intergalactic environmentalists. The strength of the combination of those two words really engaged people and other people started to ask us if they could also be intergalactic environmentalists.

LC: What are the next steps for Moon Mission and the Intergalactic Environmentalists?

JQ: For Moon Mission 2030, the educational part is ongoing but we also need to think about what the next step is in terms of actually going to the moon. For example, maybe we should start contacting space organisations.

In terms of Intergalactic Environmentalists, we are doing a project about how we can build a civilisation on Mars with a similar approach to the moon mission—a bottom-up strategy. We are building a very amateur Mars simulation and seeing how we can live inside of this dome that we are building sustainably.

We also want to create more exhibitions with other artists who are also environmentally focused.

LC: Finally, what will happen to the plastic bag if/when it comes back to earth?

JQ: We don’t know yet. We thought about recycling it into an object and displaying it or giving it back to NASA because, since they left it there, it actually belongs to them.