Content type: Essay

Credits: Text by Rebecca Altman (writer and sociologist) and photography by Dr Max Liboiron (Associate Professor of Geology at Memorial University of Newfoundland, writer and photographer). Originally published on Discard Studies.

Year: 2021

‘And so what began as a term meant to “fix the recycler,” over time, has come to indicate a broader critique of a materials system premised on disposability.’

Introduction:

In this essay, Rebecca Altman traces the etymology and the evolving uses of the term wishcycling in order to understand the shifting attitudes around recycling and plastic waste. She argues that the term is becoming useful for critiquing the fossil fuel and plastic industries as well as systems premised on disposability. Altman's text demonstrates that in studying the vernacular emerging in association with the climate crisis, we can begin to understand how attitudes are changing and what scientific or systems-based knowledge is spreading to a more public audience.

On Wishcycling

Wishcycling is the process of placing discards into the recycling bin even when there’s little-to-no chance for their recovery. The term entered common use over the last six or so years. But its usage and meaning have changed over time.

To get a sense of how often wishcycling appears in (digitised) print, I entered it into Google search. Returns ranged between 8,000 and 28,000 hits, depending on whether hyphenated and in quotes. Of course, this is far from a reliable or even valid measure, but it does hint at the term’s popularity and suggests it is worth exploring more systematically.

Wishcycling, and its nominal variation wishcycler, have varied meanings that frame the relationships among plastics, recyclers and industry differently

Paging through Google’s finds, wishcycling and its nominal variation wishcycler have varied meanings that frame the relationships among plastics, recyclers and industry differently. Among these multiple meanings, the primary difference is who or what is at the heart of the critique: the individual, the infrastructure, or industries.

Initially, the term emerged from within the recycling and waste industry as a response to the influx of non-recyclables "contaminating"

Interrogating Wishcycling

While drafting a forthcoming essay for The Atlantic about recycling, plastics and the climate crisis, I found myself wanting to use the term wishcycling. But I paused to consider it further.

What was the context and timing of the term’s emergence, I wondered? And if I use it, whom should I link to or cite?

I’d used the term once before in a published essay. I thought it clever, though I didn’t give its etymology much thought.

Back in 2018, when I was working on a cultural and environmental history of plastic grocery bags for Topic Stories, I wanted to explain the conundrum bags pose to single-stream curbside recycling programs. These rely on automated materials recovery facilities (MRFs) to sort recyclables by category and type.

It was an article in The Baltimore Sun (2018) that introduced me to the term wishcycling. In this case, it was used to explain plastic bags’ prolific presence in the recycling stream despite requests by handling facilities to seek alternatives to curbside collection.

But in the U.S., where I live, to "properly" recycle plastic grocery bags (and other plastic films), requires separate collection, including extra time and dedicated transportation to drop-off facilities. Finding drop-off locations also necessitates an Internet-compatible device and an Internet connection to access a collection site location tool (such as http://www.plasticfilmrecycling.org).

I’d used wishcycling as a critique of plastic bags and disposable plastics in general. But looking back on it now, my use in Topic strayed from how I’d initially seen it in The Baltimore Sun, where wishcycling was meant to chastise those who’d tossed plastic bags in with the rest of their recycling.

A more recent New York Times piece from Michael Kimmelman characterized wishcycling as an ‘environmentalists’ term of art’. But is it? When I started asking around, just casually among colleagues, I realized wishcycling’s origins were, for many, murky or unknown, though I got the sense the term had particular purchase within the waste and recycling industry.

The Origins of Wishcycling

Wishcycling, sometimes called aspirational recycling, emerged from the U.S. waste and recycling industry, where managers critiqued the "poor" sorting and binning practices of recyclers sending materials their way.

Wishcycling, sometimes called aspirational recycling, emerged from the U.S. waste and recycling industry

The earliest instance of wishcycling that I’ve located in (at least digitized) print was a 2015 story by the journalist Eric Roper. Roper told me he heard the term while reporting on the financial strain experienced by the beleaguered industry.

As Roper wrote, ‘Plunging oil prices and a slowdown of the Chinese economy are causing ripple effects in the Minnesota recycling market, wiping out monthly profits that cities use to drive down costs for the service. The falling price for recyclable materials coupled with changes in what people are recycling is putting a financial strain on processors and creating uncertainty about the future taxpayer costs for recycling programs.’

Roper had heard the term from Bill Keegan, President of DEM-CON Companies, a waste and recycling outfit based in Shakopee, MN. Wishcycling struck Roper as a novel term, so he wrote a follow-up piece about it, which detailed the range of items—plastic bags, yes, but also bowling balls, shredded paper, loose bottle caps, and food sachets—that made the sorting of recyclables that much more difficult to manage for three Twin Cities recycling companies.

For recycling companies, items like grocery bags increase the time and cost to sort and capture other materials deemed of value and reduce the overall profitability of the entire recycling endeavour.

I contacted Bill Keegan, who confirmed by email: ‘When I first used the term, I had not heard it anywhere else before that. I describe it as the act of “walking to the curb with something that you are unsure if it can be recycled or not, so you throw it in the recycling bin—wishing that it will be recycled.” Although often well intended, this ends up contaminating the good recyclable materials in the bin.’

The Failed Promise of Recycling

The notion that recycling, as currently organised, isn’t the panacea many, myself included, had hoped is a common topic in waste and discard studies. Frank Ackerman’s Why Do We Recycle? (1997), Samantha MacBride’s Recycling Reconsidered (2011), and her more recent, follow-up Discard Studies post—'Does Recycling Actually Conserve or Preserve Things?'—for example, make the case that recycling has neither been environmentally sound nor economically sustainable. (See also the Discard Studies overview of MacBride’s book by Max Liboiron). Yet, recent journalism has shown that the plastics (and by extension the fossil fuel) industry continue to promote recycling as a way to address plastic waste and to detract from plastics’ overproduction.

Recycling has neither been environmentally sound nor economically sustainable

From its outset, municipal waste recycling has always been piecemeal, overburdened, and unable to keep pace with the type, heterogeneity, and quantity of materials being made, MacBride argues. Absent a market, and absent a buyer, an object, regardless of its composition or its technical recyclability, is otherwise considered waste and bound for landfill or an incinerator if it doesn’t escape beforehand and enter the open environment.

In reality, the term recyclable isn’t so much an innate feature of a disposable object as it is a signifier of a relationship between a discarded object and a marketplace willing to buy and (re)process it. Indeed, plastic bags, while technically recyclable, often are not recycled. Further, the distribution of buyers and markets is uneven, which is why recycling programs are regionally specific and ever-shifting. And the recycling market has shifted considerably in recent years, given global dynamics in the import/export of recyclables for processing. The 2021 plastic amendments to the Basel Convention, which regulates the international trade in waste, may alter global recycling markets even further.

For plastics, recycling hasn’t diminished plastics production, which has continued to rise

For plastics, recycling hasn’t diminished plastics production, which has continued to rise. It hasn’t necessarily lessened fossil fuel extraction either, as MacBride wrote in this Discard Studies post:

‘With recycling—one assumes—used materials stand in for raw materials. This way, recycled content cuts down on the need to extract (conservation), which in turn prevents some of the environmental damage from extraction that would be taking place without recycling (preservation)…’

But, there hasn’t been sufficient data to coordinate, let alone determine, the relationship amongst plastics recycling, resource conservation and environmental preservation. And even if there were, MacBride engages us in a thought experiment:

‘Let’s say more Americans recycled their plastics, and this resulted in an influx of more recycled plastic onto the market. Even with robust closed loops achieved, does anyone really think that the executives at one of these multinationals would get to the point of saying, “well, you know, it’s good that the need for input materials is being met by recycled plastic… that means that this year we can scale back production a bit.”’

What’s more, precedent suggests that ‘when you increase efficiency in production and consumption, you may well see an increase in overall extraction,’ MacBride adds, citing the Jevon’s Paradox.

Indeed, according to the International Energy Agency, as of 2018, the plastics industry is banking on growing plastics and petrochemicals production to sustain future growth in oil and gas production. In fact, the IEA reports, as energy and transit systems shift toward renewables, petrochemicals and plastics ‘are rapidly becoming the largest driver of global oil consumption.’ Petrochemicals, notes the IEA,

‘are set to account for more than a third of the growth in oil demand to 2030, and nearly half to 2050, ahead of trucks, aviation and shipping. […] Petrochemicals are also poised to consume an additional 56 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas by 2030, equivalent to about half of Canada’s total gas consumption today.’

Part of this is because there remain distortions in the price of fossil fuel-based feedstocks and the plastics synthesized from them. There are multiple dimensions to this. First, the plastic (and waste) industries have appropriated or presumed unlimited access to land to serve as the "away" in throw-away disposability (see Max Liboiron’s Pollution is Colonialism). Nor has industry had to factor end-of-life costs (and consequences) into their bottom line. Further, policies have subsidized oil and, more recently, fracked gas production, which in turn has kept their byproducts, naphtha (from crude) and natural gas liquids, cheap. From cheap feedstocks flow cheap plastic, roughly 40% of which is directed into disposable uses like short-term packaging and single-use containers.

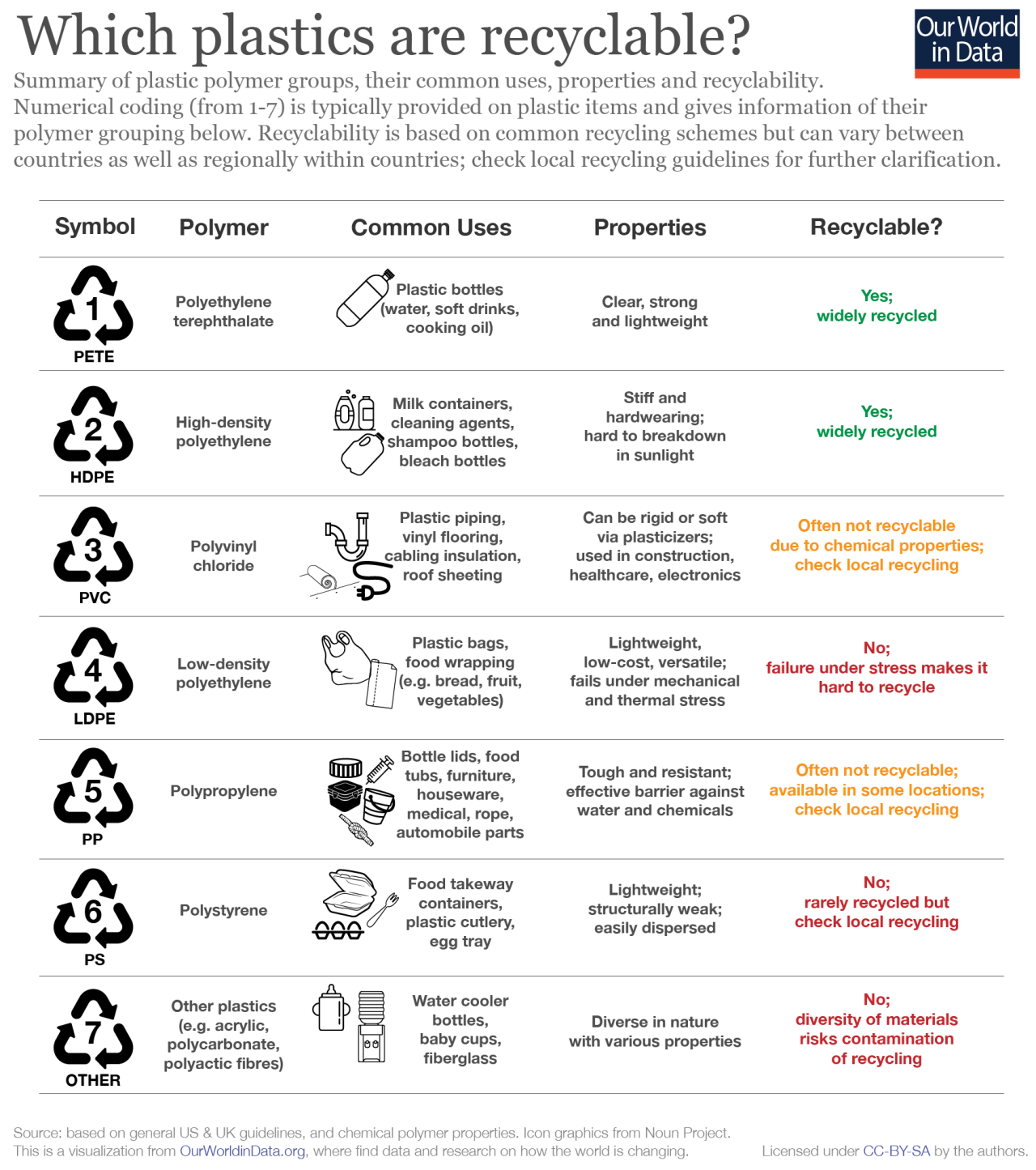

As a result, many big brands and manufacturers have opted to use virgin rather than collected recycled plastics because they are less expensive (though this may be changing, see, for example, this P&G announcement). Most plastics (numbered three and above) produced today have little to no end-market and/or were not designed for recovery in the first place, though they may still appear with a recycling symbol stamped onto them.

In fact, the labelling system can be misleading to recyclers. In the U.S., for example, consumer-facing plastics appear with a resin identification code stamped on their inverse, a number that identifies the resin type and (until recently) the chasing arrow symbol synonymous with recycling. For many, the label implied that this specific item is universally recyclable, which likely has contributed to the hard-to-manage recycling stream and led the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), which administers the U.S. labelling system, to replace the recycling symbol with a plain, equilateral triangle.

‘Changing the marking symbol […] decouples the [resin identification code] system from the recycling message, which has been a significant source of confusion for the public,’ noted Bridget Anderson with the NYC Department of Sanitation, who participated in the task force at ASTM that decided to change the codes back in 2013.

Give all this, what Keegan and colleagues are communicating is that the recycling infrastructure is straining to keep pace with the scale, composition and sheer complexity

Wishcycling and The Deficit Model

Historically, rather than altering the scale and composition of the increasingly complex waste stream they manage, the waste and recycling industry and their allies in government, have put their attention on discarders—their knowledge, their skills, their habits, their behaviours.

Wishcycling, some in the industry argue, could financially sink recycling altogether. ‘There is a direct correlation’, wrote Waste Management Magazine in 2020, ‘between escalating residential wish-cycling and accelerating costs for recycling programs. The only way to ensure that your program remains functional is to step in with modern educational initiatives and tools to improve resident behaviour’.

Such a position individualises the problem and operates within an assumed information deficit, which has had a lasting and influential presence in public discourse. This is the case in public health (consider the difference between anti-smoking campaigns that seek behaviour change versus anti-tobacco industry campaigns like The TRUTH).

The deficit model is also evident around climate change (see the work of Julie Doyle and colleagues on BP’s backing of the "carbon footprint") and littering (i.e., ‘don’t be a litterbug!’ as explained by Susan Strasser and Samantha MacBride.) In all cases, individualisation shifts attention and agency for waste issues from industry and systems to individuals and their knowledge and habits.

Wishcycling memes and media also follow this trend, locating the failings of recycling within the individual and not institutions, infrastructure, or industries overproducing disposable goods in the first place: ‘Are you guilty of wishcycling?’ Fix your ‘sloppy green habit!’ Deal with your ‘well-intentioned reflex,’ your ‘bad habit.’ In 2018, YahooNews! ran a story that read: ‘Contrary to popular belief, a recycle bin is not a wishing well or a lucky Italian fountain in which you toss coins, and your local recycling facility workers are not wizards who magically transform something completely unrecyclable into something that is.’

Though they promote recycling, deficit-model wishcycling education programs do so with the paradoxical message: recycling less makes recycling more effective. As Bill Keegan told me, ‘the mantra needs to be, 'when in doubt, throw it out', which is a hard message for people to hear at times.’

Punitive measures, including fines, are then used to reinforce the message: ‘Recycling collectors will put Smither’s wish-cyclers on notice,’ read a 2019 headline in The Interior News.

Wishcycling’s Evolving Use

But the term has been taken up by those outside waste and recycling, where its meaning has begun to shift.

I want to thank Bhava Shamasuder, a professor in the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy at Occidental College, who, in a conversation about wishcycling on Twitter, helped me arrive at this realisation. Bhavna explained that, because of COVID, her local grocery, like many others, banned the use of reusable shopping bags and promoted plastic ones in their place. In response, she started bringing the bags back for recycling in the bins the store provided. But this, she said, felt like an act of wishcycling. If she does as instructed—places this bag in this bin—will they really be recovered and, in some way, recycled ? What actually happens to the bags stores collect?

What’s at the core of this instance of wishcycling is an awareness that there may be no effective remedy for the disposables consumers cannot readily avoid or refuse.

Consider more examples culled from my informal digital gathering exercise. Note the object of the critique, which is no longer focused on the "misinformed", or the "ignorant" and "idealistic" recycler, but on the institution of recycling, how its infrastructure and policies operate, and more, the promise and promotion of recycling by the plastics industry as the solution to worsening plastics pollution.

- Stephen Buranyi, writing in The Guardian (2019), noted: ‘The government was stuck picking up the tab for the industry’s previous big talk on recycling. And the public was happy as long as someone was taking out the trash. To this day, some environmental campaigners refer to household pickup as wish-cycling, and recycling bins as a “magic box”.’

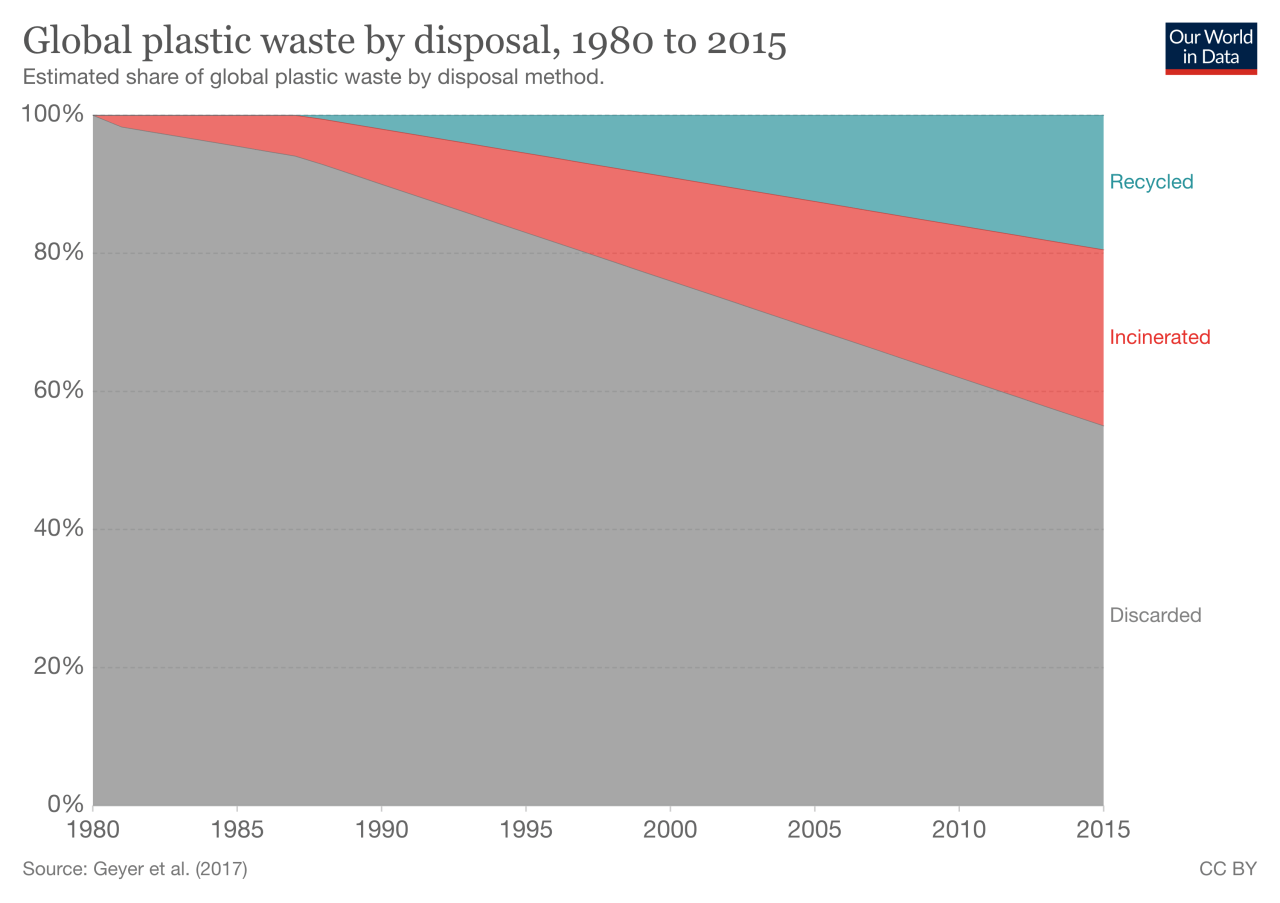

- ‘Plastics are commonly tossed into mixed-recycling bins to be conveniently collected and—we incorrectly assume—remade anew,’ wrote Stephanie Borrelle in The Conversation (2020). ‘The reality is that we’re wishcycling. In fact, less than 10 percent of plastics are recycled.’

- ‘The eight percent of plastics which, in 2017, were recycled… were sent to China, in a national approach to wish-cycling.’ This excerpt is by Natalie Keltner-McNeil, who wrote about the environmental justice implications of past and present recycling practices for The Leaflet, a newsletter put out by the Student Environmental Resource Center at UC Berkeley.

- ‘Companies continue to put the onus on people,’ argued Greenpeace’s John Hocevar in a 2021 Bloomberg letter-to-the-editor. He notes how companies push recycling despite its significant limitations and mislead customers through labelling, which in turn, he says, is ‘encouraging people to wishcycle by placing everything in the blue bin,’ which ‘makes it much less likely for truly recyclable items to be recycled and degrades the efficiency of recycling systems.’ At the centre of the lawsuit are polypropylene (plastic no. 5) yoghurt containers, a type of plastic for which there is a limited, highly variable and regionally-specific markets for its collection.

Like Bhavna’s comment, these examples highlight a subtle but significant shift in the term’s meaning as it has moved out of industry into media and wider use: from a behavioural critique of wishcycling—that is, recycling an item not knowing whether that item is recyclable—to a systems critique—wishcycling while knowing a so-labelled "recyclable" item isn’t likely to be recycled after all.

This shift parallels a cascade of research and reporting that have further revealed to the public the mismatch between the problem (particularly as it pertains to plastics and their evergrowing production) and the principle political solution pursued to resolve it (recycling). In 2017, Geyer, Jambeck and Lavendar Law created a model that estimated only 9% of the plastic manufactured since 1950 had been recycled, which called into question what, in fact, current recycling systems had been doing to impact disposables.

The following year, in 2018, China announced policy changes that would reroute the global import of recyclables as it no longer accepted most classes of recyclable plastics, which drastically shifted the economics of recycling markets for nations reliant on their export to China and rippled into communities. Some US communities, for example, lost curbside recycling services. Others shifted from single-stream back to sorting paper and metals separately from plastics (for example, see this story from the Cape Cod News, Massachusetts).

Then in September 2020, mid-pandemic, Laura Sullivan at NPR published her interviews with plastics’ lobbyists, who confessed, as far back as the 1970s, the industry invested millions on ads promoting recycling’s benefits, even though they knew recycling wasn’t a viable answer.

My hunch is that wishcycling evolved within this window and because of growing public concern over disposable plastics. And so what began as a term meant to "fix the recycler", over time, has come to indicate a broader critique of a materials system premised on disposability.