Content type: Essay

Credits: Alison Carter (Alumna, BA in English Language and Culture with a Minor in Digital Humanities, Leiden University, 2019)

Year: 2019

Introduction:

In this text, Alison Carter zooms into two seemingly inconsequential pieces of space junk—golf balls. Using material analysis and historical transcripts, Carter questions the efficacy of leaving items on the Moon and how this act reflects our species' attitudes to litter on earth.

‘These are both a testimony to the human species’ desire to play and its propensity to litter.’

Since 1971, two golf balls have sat abandoned and undisturbed on the Moon. They are a testimony to the human species’ propensity to play— but also to litter. During the Apollo 14 Moon mission (31 Jan–9 Feb 1971), astronaut Alan Shepard secretly took them with him along with a research instrument that could be adapted into a six-iron golf club with the intention of creating a playful televised stunt—‘a little sand-trap shot’ that would neatly illustrate weightlessness for the folks back home.

NASA did not sanction his actions. Shepard effectively took a unilateral decision to alter the Moon’s surface by leaving behind a foreign object. Perhaps Shepard never considered that leaving golf balls on the Moon could be termed littering rather than just the inevitable fallout of a scientific experiment. To Shepard, they were, after all, only two little ‘white pellets’, as he referred to them, that were innocuous and ‘familiar to millions of Americans’.

A new far-flung golfing destination for future wealthy space tourists. An act of personal curiosity and play. An aesthetic, poetic, and popular cultural metaphor—a tiny golf ball marooned on the Moon. Despite being one of the most trivial objects abandoned on the Moon, it is also one of the most iconic. It illustrates humanity’s capacity for frivolity and plays in the face of a sublime and immense Universe. Looking up at a full moon, with its pitted and pale white surface, the Moon even seems to resemble a dimpled golf ball that has been struck and landed a short distance from Earth.

Golf balls are inessential to immediate human survival

Golf balls are inessential to immediate human survival. Nevertheless, they have a long history of consuming time and material resources in their design. According to Golf Ball History, the first golf balls from the fourteenth century were wooden, and thereafter various natural materials like leather, cows’ hair, and chicken and goose feathers were used. In the twentieth century, rubber and caustic liquid cores were used until it was realised they led to eye injuries if balls were tampered with. In the 1960s, synthetic materials replaced earlier natural materials. Contemporary designs include varying diameters and depths of the dimples, ball weights and materials used to increase aerodynamics; embedding balls with radio transmitters for location purposes; and manufacturing recycled balls or biodegradable balls in response to environmental concerns.

![Image from the project EEN BALLETJE SLAAN [HIT A BALL] by Nienke Temmink](https://www.kabk.nl/storage/lectorates/design/Design-in-the-Deep-Future/Space-junk/Space-Junk_Golf-Balls_Alison-Carter_Ninke-Temmink.png)

The locations of the Moon golf balls are known and could, in theory, be recovered. NASA’s Apollo 14 Image Library and photographic archive shows they are located near the USA flag. If the balls were ever brought back to Earth, one could imagine their second life would be as a museum exhibit on US heritage or in the private collection of a wealthy golfer. But if the golf balls remain on the moon, what will their life hold? Will they decay? And, what kind of problems might they cause?

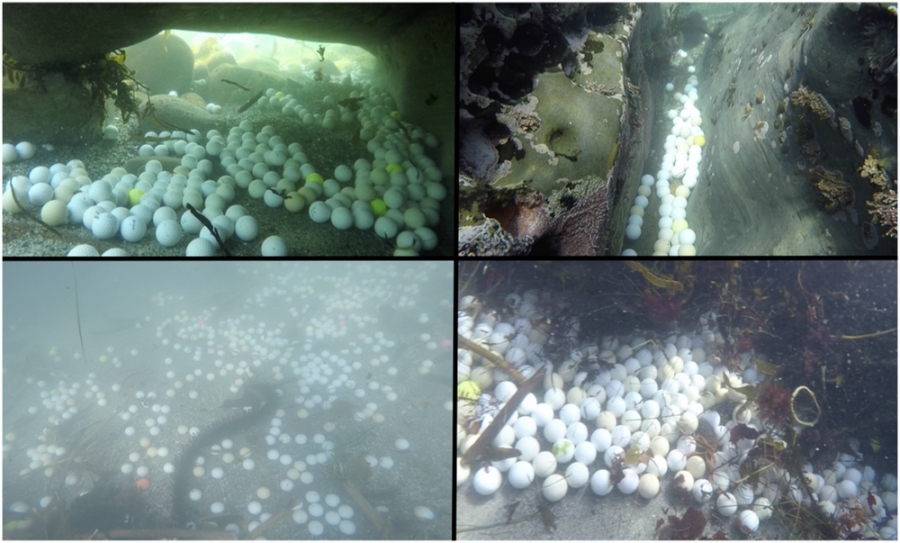

On Earth, there are already environmental problems associated with lost and discarded golf balls. It is common for a golfer to lose a handful of balls during a game, and this seemingly inconsequential (if frustrating for the golfer) problem scales up. There is a rapidly growing problem of contaminating rivers and oceans because of debris from degraded golf balls. These golf balls leach zinc, microplastics and other chemicals into their surroundings. In ON PAR; The Burden and Boon of Lost Golf Balls, journalist Bill Pennington explains:

‘No one knows for sure how many golf balls are lost each year worldwide, though the total in the United States is estimated at 300 million. Hundreds of thousands of golf balls are lost or abandoned every day in lakes, ponds, forests, wetlands, deserts, backyards, gardens, parking lots, cemeteries, on rooftops and at the bottom of woodchuck holes.’

Of course, the environmental conditions on the Moon are different to those on Earth, and it is not clear if a golfball would decay in the same way. If they don’t, then what would future human generations or alien-life forms make of them? Would an alien even recognise that this dimpled machine-tooled sphere was for play? Would they understand the concept of play? An alien might be just as mystified as an otter foraging for food, picking up a golf ball on a Californian shoreline. An alien might suppose a golf ball was some sort of communication device, or weapon, or medicine, or a system of exchange, or some strange crystallization of elements, or a source of dangerous contamination.

The balls at present are part of an archaeological space site, and possible future tourist attraction or pilgrimage site for a new wave of post-human astronaut golfers. Perhaps we can also see them as a warning of how our seemingly inconsequential playful actions can impact environments.

In 1971, it is unlikely that golfers even knew they should be worrying about where their golf balls ended up when they were lost or outlived their usefulness. Indeed, the ecological movement and understanding around our impact on the planet were only just beginning. In 1972, the iconic blue marble photograph was taken on another moon mission by the Apollo 17 crew, which spurred on this new ecological awareness. For the first time, the public saw our planet from afar, and the earth looked strangely fragile, breakable. Now, more than 50 years later, we have a much more thorough understanding of the ecological crisis at hand and yet, our actions still sit in conflict with the necessary steps that need to be taken to avoid a climate catastrophe. The question is, will humans be able to prioritise the environment overplay?