On 16 May 2018 Rosalien van der Poel presented a Library Lecture on the topic of ‘Chinese export paintings’

Albums with 19th century Chinese figurine paintings

Chinese export painting

The three albums with Chinese paintings from KABK Library are so called ‘Chinese export paintings’. These kinds of paintings were largely intended for trade and export in the period of the historical China trade that is, around the 1730s to the mid-nineteenth century and long after.

A western term

The term ‘Chinese export painting’ was coined by Western art historians only after 1950. It references the fact that these works were made for export to the West. These paintings were described by their makers as ‘foreign paintings’, ‘foreign pictures’, ‘paintings for foreigners’ or ‘Western-style paintings’, whilst foreign, Western buyers in that period just called them ‘Chinese paintings’.

Pictorial souvenirs

Albums with watercolours on pith paper were a desirable souvenir in 18th and 19th century China. To show friends and family at home where they had been and what they had seen, visitors sought inexpensive pictorial souvenirs: small, light and easy to carry home. Watercolours were painted and sold in studios, shops and stalls in the Cantonese area where the foreign traders were housed.

Watercolours could be purchased either as loose leaves, or as sets of twelves leaves bound in an album. The cardboard covers of the albums were sometimes covered with embroidered silk or with woven textile with geometric patterns, like this one from KABK Library.

Export painters and their studios

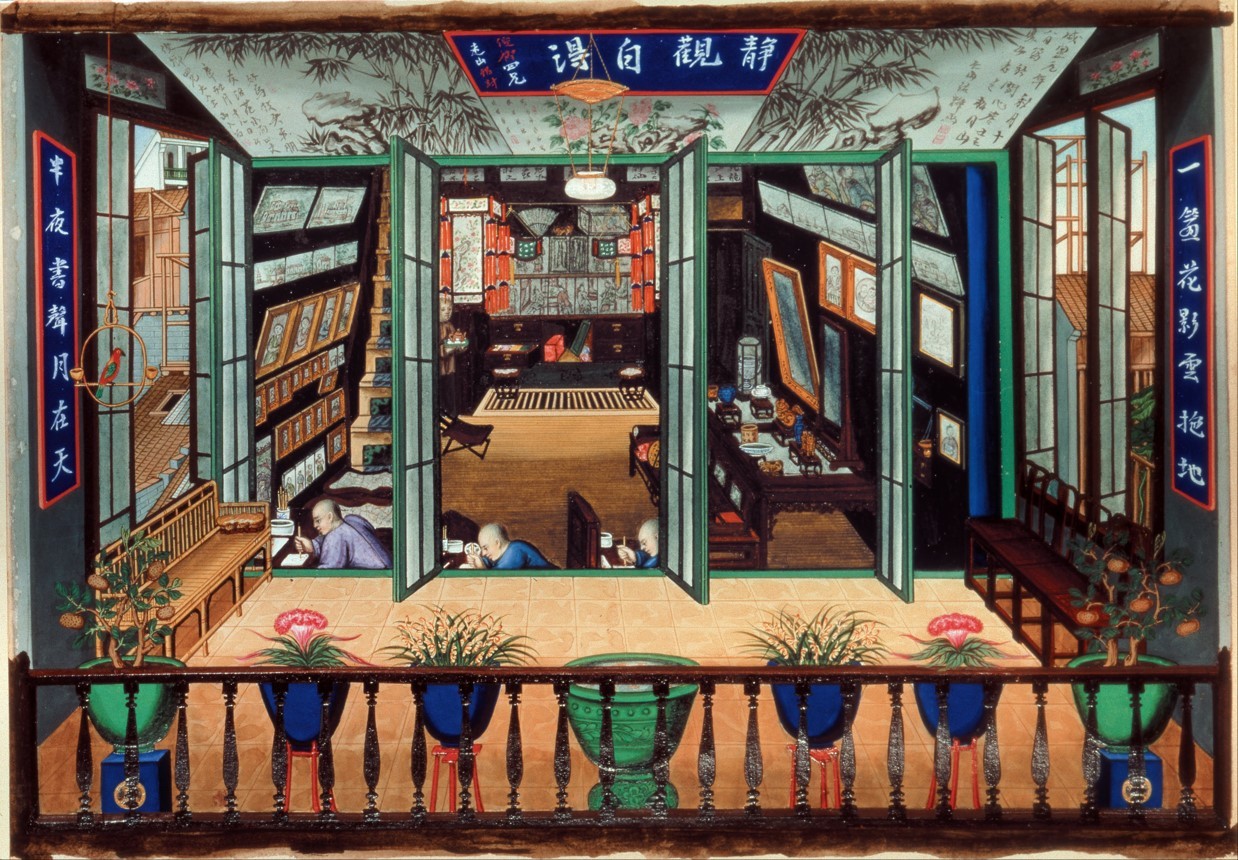

Precisely how many artists and studios were located in Canton is not known. The studios of the Chinese export painters Tingqua and Lamqua were the most famous. An impression of how such studios may have looked like is shown on this picture.

Observations of Western visitors on this painting practice in the period 1800-1850 give an ambiguous picture. Some mentioned that there were about 30 painting studios in Canton, where you could buy pith paper watercolours (Lee Sai Chong, 2005). Another record writes about the studios as factories where the production of export paintings was carried out by ‘between two and three thousand pairs of hands’ (Williams, 1856).

Figurine paintings

The extant copies of Chinese figurine paintings in the Dutch public collections (o.a. in Amsterdam Museum, Tropenmuseum Amsterdam, Deventer Stadsarchief en Athenaeumbibliotheek (SAB), Museum Volkenkunde Leiden, Zeeuws Museum Middelburg, Wereldmuseum Rotterdam en KABK Library) tell us that Dutch China-goers had an interest in images of Chinese people and the clothes they wore. Figurine paintings are characterised by a great degree of uniformity. You can find exactly the same paintings with only a change in the colours. This means that it is likely that a great deal of work was done with templates or tracing techniques. More frequently, however, drawings were done freehand within a standard repertoire. The outline of the position and accessories of a Manchu prince (chair and footstool), for example, was often repeated. As shown on the pictures, the colouring and the details differ. In addition to the clothing, it is also the associated attributes, for example a musical instrument.

If we compare watercolours from different albums in Dutch public collections, we’ll notice that these paintings are expedient examples showing the individual traits of each image and the painter’s own input in the end result. The type of figures show constant elements, but the execution, done by individual artists, varies greatly in all kinds of details.

Click on the images below to see which collection they belong to.

Constant elements in these figures depicting a lower rank Mandarin are the headgear with the button, the shoulder cap and his blueish gown. It is clearly visible that each painter executed this figure in his own style.

In these figures the constants are the same in the picture of a high-ranking Mandarin, recognisable by his dress and his headgear with a peacock feather and his sitting position. All the chairs and the facial expressions (with and without moustache), however, are different. The use of colours also varies.

Illusionistic images

The men and women pictured in the figurine albums show their richly decorated clothing and head and hair adornments in detail. We must bear in mind that the painters may never have seen officials in full court dress and were probably more interested in attracting their customers than in strict accuracy.

Twentieth-century researchers write about the fact that Chinese export painters were apparently prepared to mis-represent aspects of their own culture. These unrealistic images were made in order not to disillusion Western buyers, and therefore these kinds of illusionistic images became ‘articles of knowledge’. Indeed, Western knowledge about China was principally shaped by these images.

Pith paper

The Chinese watercolours from KABK Library are painted on pith paper. From the 1820s pith became a familiar material in Europe. Because of its thinness, delicate, translucent appearance, and velvety surface, pith is often mistakenly referred to as rice paper. However, pith is actually unprocessed plant material cored from the stem and branches of a shrub native to regions of Taiwan and Southern China: the Tetrapanax Papyrifera (tóng cáo zhĭ).

This video found on YouTube shows how pith was taken from the stem of the Tetrapanax Papyrifera and how it is made suitable for painting.

The internal order of pith resembles the honeycomb structure of a wasp's nest. This complex cellular structure makes pith highly reactive to moisture. When paint is applied to the paper's surface, the cells swell, causing the painted image to take on a three-dimensional appearance with a jewel-like brilliance. This gives a special and typical effect. While stunning to look at, pith paintings can be very vulnerable.

Framed with a silk ribbon

After the images were painted on the pith paper, paste is applied at the back of the four corners and the painting is lined with a sheet of paper. Four strips of textile - usually silk - are pasted around the image to form a frame. The sheets are then bound into an album.

Sources

Lee Sai Chiong, Jack, China trade painting: 1750s to 1880s. Dissertation. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, 2005

Williams, Samuel Wells, Chinese commercial guide, consisting of a collection of details and regulations respecting foreign trade with China, sailing directions, tables. Canton: The Chinese repository, 1856

Personalia

Rosalien van der Poel

Rosalien van der Poel presented a Library Lecture on this topic on 16 May 2018. Rosalien is Institute Manager of the Academy of Creative and Performing Arts (ACPA) at Leiden University. In November 2016, she graduated as a PhD with the dissertation Made for Trade – Made in China. Chinese export paintings in Dutch collections: art and commodity (available in the KABK Library). Furthermore, she’s a research associate China at the Leiden Museum Volkenkunde, part of the National Museum of World Cultures, and a board member of the Royal Asian Art Society in the Netherlands (KVVAK).

Rosalien van der Poel: ik wil de Chinese exportkunst graag nog een keer laten ‘shinen’