In September 2017, the Master Industrial Design was launched at the Royal Academy of Art, officially transforming the first study programme in the Netherlands in industrial design – which dates back as far as 1950 – into a master’s degree programme. An interview with designer and head of the programme Maaike Roozenburg about the interface between technical and artistic education, the curriculum of the new Master Industrial Design programme and the role of the designer in our society.

Maaike Roozenburg (Delft 1979) studied art history at Utrecht University for two years before transferring to the DesignLab of the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. Her work focuses on how we deal with and restore our cultural heritage. In this, she always operates on the interface of design, conservation and new techniques. Roozenburg has been the head of the Master Industrial Design programme at the Royal Academy of Art (KABK) in The Hague since 2017.

Interview by Merel Kamp

'Designers must declare their position'

Why has yet another new master’s degree programme been launched in the Netherlands? How does this programme distinguish itself from other postgraduate study programmes at universities of technology and art academies?

‘There is a gap between technical design education, on the one hand, and artistic design education, as taught at art schools, on the other hand. Technical education considers technology as a given and invents applications for this within the confines of technology; it does not question technology. Artistic education takes ideas and design as its basic premise, but frequently does not take sufficient account of technology and production systems. We aim to bring these two together in the Master of Industrial Design at the KABK, in which the focus will be on questioning technology and the industrial system in a product. If you learn to think and design in this way, you can make changes.’

What needs to change?

‘The system that we, roughly speaking, developed during the Industrial Revolution on which to base our economy, which depends on growth and the continuous large-scale acquisition and production of consumption goods; needs to be reviewed. At present, it creates more problems than it resolves. The focus has shifted from human needs to keeping the system in operation by creating needs. This is actually quite perverse.’

Designer Babette Porcelijne recently said in an interview that not scientists but designers should show us the way forward in coping with our contemporary problems. Do you agree with her?

‘I do not believe so strongly that design can solve all problems and designers are the big problem solvers of our present society, which is something you frequently hear being said today. It becomes interesting if designers translate the knowledge developed by scientists into visions of an alternative way of doing things. Designers can contribute to change by developing products that question the system and opening up new pathways.’

Have design and design education therefore become activist by definition?

‘You can no longer afford not to take a stance. Whichever way you look at it, you must be aware of the consequences of your actions as a designer. Of course, you can still decide to make polluting, fast-selling rubbish, but not without stating a reason for doing this. In terms of education, it means that students will need to define their relationship to the social debate. Practically speaking, this means that you have to teach your students to read scientific and other articles, and to regard these with a critical eye. After two years of studying, students have to know where they stand and what they stand for. This means that they must also have a clear grasp of how production systems work. In this, they needed to look at the technical side of things as well as the significance of this production technology.’

Why do you believe that a master’s degree programme at an academy of fine arts would be the best place to learn this?

‘Science has its limitations. The methods are fixed and, as a scientist, you need to satisfy certain rules and regulations. This makes scientific knowledge reliable and broadly applicable. However, the domain of meaningfulness is difficult to investigate according to fixed rules and methods, simply because something like meaningfulness does not stick to rules and is subject to change. Within the discipline of artistic research, or design research as we call it, this is much easier. You can ask questions about the sense and value of the available production and other technology. Not only the economic value, but also the value for the development of meaningful, aesthetic and sustainable products with a positive impact on our society.

The research method is free and, as a result, students are able to set to work in an intuitive and creative manner. The results obtained by scientific research can provide interesting input in this. I therefore think that bringing together the scientific, the technical and the artistic will yield far more than when everyone is operating entirely independently from one another. If you want to do something that makes sense, you must collaborate at interdisciplinary level.’

How is all of this reflected in the new master’s degree programme?

‘Design research and/or artistic research is part of the curriculum of this master’s degree programme, in addition to theory, communication and, of course, design-related subjects. Students learn to formulate research questions and collect data, among others. Additionally, we seek collaboration with external parties every semester, such as research institutes, universities and the manufacturing industry.’

Can you describe a collaboration project with an external industrial party?

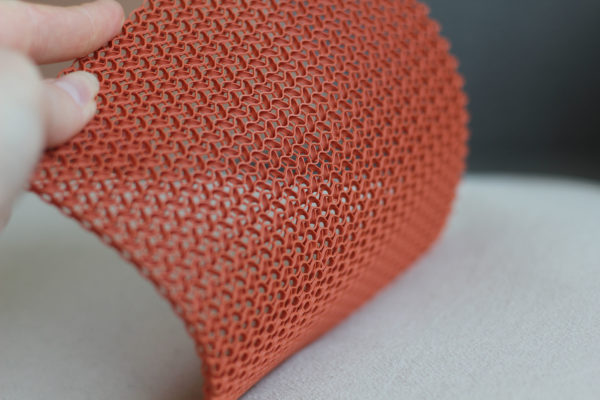

‘Next semester we will be joining forces with Smart Robotics, a temporary agency for robots. They are interested in examining the useful application of robots. The agency noted a certain resistance among humans to working together with robots. A solution for this problem could be to make robots look different, more human. But this is a very limited solution. What you should actually be asking is: where would it make sense to use robots? Robots make it possible – because this is profitable – to bring production processes back to the Western world, for example. Next, it is interesting to see if you can design a product that will make people understand that working together with robots at local level makes sense, or even make them enjoy doing so. With an operation like this, you – as a designer – can change the significance of the robot for humans at a more fundamental level than by giving a robot eyes and painting a smile on its face.’

Doesn’t this quickly lead to designing systems or processes rather than products?

‘That could happen. Still, it is interesting to retain the concept of a tangible product. That product almost becomes a sort of plea for a new production method. I believe in the power of tangible manifestations. People are physical beings and relate differently to an object than to an infographic or a scientific report, for example. An object – as a conversation piece or something that can be used – is much richer and has a far greater power of expression. This imagination is the primary discipline of the designer. Purely analysing processes is something that others can do just as well, if not even better.’

For which students is the post-graduate programme intended?

‘Students who harbour not only a fascination for technology and the world of design, but also want to examine both with a critical eye; who are motivated to be both a part of production processes and a co-designer. Students who want to develop their skills as well as their vision. These students will feel at home in this master’s degree programme.’