Bas Froon (1978) graduated from the predecessor of the Master Industrial Design, the Post Graduate Industrial Design, in 2017. He participated in the Dutch Design Week in 2017 and will be making an appearance at Salone del Mobile in Milan this April.

Froon studied technical administration and worked as a commercial manager at an energy company for almost 10 years before deciding to change direction and focus on design.

“I had a good job but eventually had enough of looking at the world via Excel sheets. I was looking for something more tangible.”

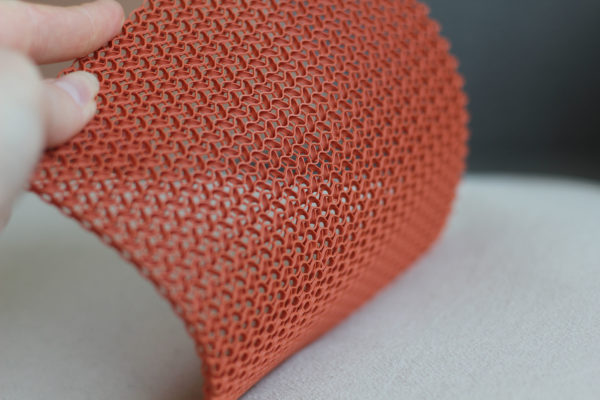

Micromoulding Soft Biocomposites

Can you talk about your graduation project?

“I graduated with a conceptual machine that allows you to locally process soft biocomposites using a hot lamp and a strong plastic; I call the technique ‘micromoulding’. I made a baby carrier as an example but the technique can be applied in many different ways. The interesting thing is that you’re able to use one type of material in a variety of differently. Otherwise you would need to use two or more materials to achieve the same result.”

How’s it going with the project?

“Since graduating it’s been quite challenging. Sometimes I feel insecure and I ask myself, ‘Are things really going well?’ But at the same time, I was asked to present my work at Dutch Design Week in 2017 and I’ll be in Milan this year. That’s definitely something! I’m currently working on expanding my network and promoting my product. During your studies you don’t realise that you won’t actually be doing a lot of designing after graduation; you’ll be focussing on acquisition, writing research proposals and applying for grants. I see this time as an investment. I really have to push myself and that’s not always easy.”

What characterises you as a designer?

“I’m very passionate about craft and manual labour. I used to restore old timers for fun. During my time at the KABK, I studied glass blowing, metalworking and tufting (a product technique for making floor carpets). I’m fascinated by ‘industrial craftsmanship’, or the translation of traditional production techniques into industrial-digital processes.

Aren’t most traditional product processes already translated into an industrial process?

“Yes, of course, on a large scale. But what I’m interested in the possibilities of local industrial productions and experiments. When it comes to production, there’s still a large gap between massive offshore production lines, like that of IKEA, and the local, small-scale, often artistic production of designers and artists. There’s not a lot in between. But that’s the area that interests me, the medium-sized ‘customised’, serial productions. The techniques that you need for that, like electronics, sensors and associated software, are becoming much more affordable and therefore accessible to individual designers.”

Would you call it a kind of democratisation of the means of production?

“You could see it like that. The emergence of the so-called ‘maker community’ on the Internet, where knowledge and experiences are exchanged and open-source platforms like Arduino – which enables amateurs to build and programme simple robots – have been invaluable. I was able to build the ‘micromoulding’ machine at home with the information I could find online and parts of existing devices. Everyone can potentially start their own product line in their garage.”

What’s the advantage of local, medium-sized, serial productions?

“The advantage of this way of producing and designing is that as a designer, you can be much more involved with the production process. When the distances are smaller and the connections are shorter, you can be more flexible and allow for innovation to take place. Local production can also be more sustainable – when you don’t get your materials from the other side of the world.”

Is that important to you as a designer? Do you think designers today have a moral obligation to design sustainably?

“I think it’s a difficult topic. Personally, I have a love-hate relationship with ‘circular design’; terms like circularity and sustainability were misused as marketing tricks in my old line of work. At the same time, you cannot avoid it as a designer today. You are responsible for the products you make, not just at the time of sale but during the product’s entire lifetime. You can make a nice bar stool or a beautiful vase but not without asking yourself questions about the origin and future of the materials being used.”

How would you say your studies at the KABK contributed to your development?

“In a way, the programme was like a pressure cooker; it put everything into focus. Thanks to the teaching staff, my fellow classmates and the programme material, I felt like I was constantly forced to explore my own boundaries. Sometimes I went too far and ruined it but often my limits were pushed in a way that helped me grow. Finding the balance between being open to criticism and feedback from colleagues and teachers and sticking to my own intuition and conviction was always a challenge. Push yourself without loosing yourself. You have to fail at that a few times to really learn how to do it. That’s so great about programmes like this; failure is accepted.”

Do you have any advice for future Master Industrial Design students?

“The saying, ‘You get out of it what you put in’ really applies to this programme. There’s not a programme out that can guarantee success but if you work hard and really go for it, good things happen. Under the guidance of an enthusiastic team, you will get the opportunity to build a strong portfolio. That portfolio will be the business card you will really need when you graduate.”

Interview by Merel Kamp