Content type: Interview

Credits: Joanna van der Zanden (independent curator and guest tutor, MA Industrial Design, KABK). Interview by Arno Eiselt (current student, MA Industrial Design, KABK)

Year: 2020

‘At the moment when a product breaks, our relationship with it intensifies.’

Introduction:

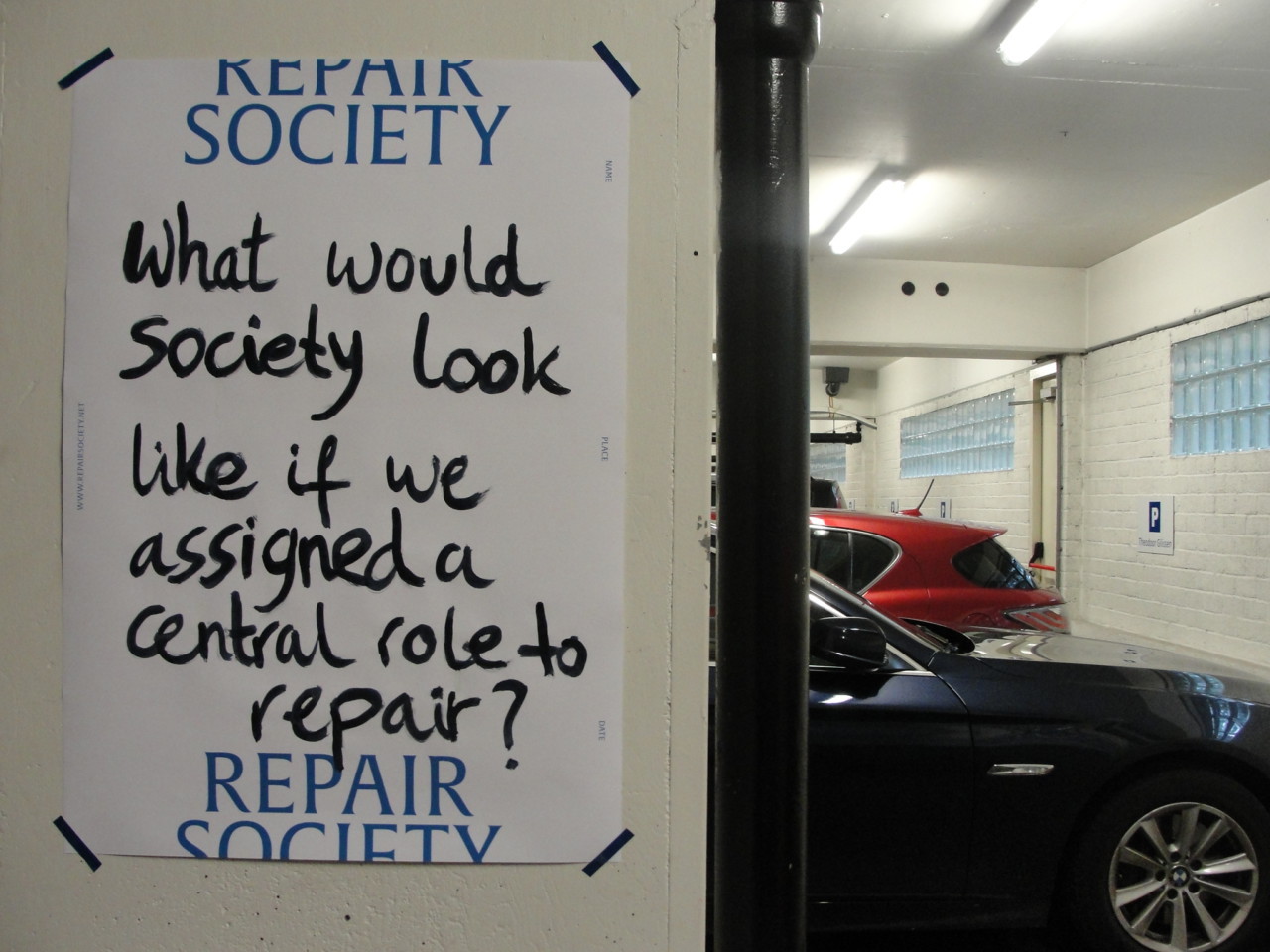

In 2009, Joanna van der Zanden helped to write the seminal Repair Manifesto, which positioned repair as a solution to the mounting problem of waste. More than ten years later, she continues to be fascinated by and advocate for repair.

In the following interview, conducted by Arno Eiselt and published as part of the MA Industrial Design Department's online exhibition Want the Unwanted, van der Zanden discusses the need to continue investigating repair and the responsibility of designers, makers and manufacturers in furthering the cultures of repair.

Open It Up, Go On an Adventure

Joanna van der Zanden is an artistic director at De Modestraat, an ‘artistic breeding ground’ in Amsterdam North, which hosts and plans cultural, artistic and social projects. She is an avid advocate of a repair society—a society which, in contrast to ours, focuses more on prolonging a product's life span. With significant hands-on experience in the field of repair and sustainability, she was able to provide valuable insights, food for thought and critical feedback in her mentorship of the students of the MA Industrial Design department during their first semester at KABK.

Arno Eiselt: You're an independent curator with a focus on socially engaged art and design and participatory practices. One of the ways you do this is at De Modestraat in Amsterdam North. What do you do with that foundation?

Joanna van der Zanden: At De Modestraat, we collaborate with a lot of volunteers and resident artists to create projects for people in the local neighbourhood. The aim is to work together and connect people. We believe that through design and art, we can get to know our neighbours in a different way whilst helping to create a more social society. To sum it up, creativity opens us up to become more aware of strangers who we didn't know before. With this idea in mind, we try to attract people from all areas of society. The neighbourhood we are located in is currently undergoing a lot of change while Amsterdam is steadily growing, resulting in an increasing number of people from downtown coming to live here. The space we are located in is called 'the breeding grounds'. It is a temporary location, given to us by the City Council, providing local artists with a space to work. It can be seen as a cultural incubator with the goal of giving back to the neighbourhood.

For us, design was less about the aesthetics of an object and more about designing as an activity

AE: Are the projects you are working on with the communities there related to repair?

JVDZ: The projects we initiate here can have various topics. But I became interested in repair as a topic in 2009 while I was the artistic director of Platform 21, which was an incubator for a new design museum that was supposed to be built at that time. Through this incubator, we were experimenting with different formats of design exhibitions as well as rethinking what the role of designers in our society should be. For us, design was less about the aesthetics of an object and more about designing as an activity. We believed that the making and the process of design is something that connects amateurs to professionals. This is something that is of great interest to me personally because most products are being designed by professionals but repaired by amateurs.

The topic of repair is also a topic about brokenness and imperfection. One could say that design has traditionally been focused on the perfection of aesthetics, but when things break down and have been repaired, they don't usually look as perfect anymore. However, they get a whole new character and charm from this process.

I like to find products to care for, and in that sense, care plays a big role in my work

AE: Could you speak a bit more about why you became interested in repair at that particular moment in time?

JVDZ: At that time, recycling was a buzzword. However, my colleagues and I were conscious that recycling things still contributes to products and materials being thrown away. It was during that period that I wrote the Repair Manifesto. The questions I was asking, and continue to ask, myself are: What are our responsibilities as designers and what roles do products play in our lives? At the moment when a product breaks, our relationship with it intensifies. It is then that you realise what meaning this product brought to your daily life. Once it stops functioning, there are a lot of questions you have to ask yourself: Can I repair it myself? Who else could repair it? Should I throw it away? Should I replace it? Or should I keep it broken? I am interested in all of these questions.

AE: What impact did the repair manifesto have?

JVDZ: Martine Postma was inspired by our manifesto, and she opened the first Repair Café in 2009. Within ten years, the number of these repair cafés has grown to over 2000. They provide a workspace for people to repair their products in collaboration with knowledgeable volunteers. In essence, there's a strong emphasis on a social aspect as well. In our Western society, the culture for repair has disappeared, and we have become (miss-)focused on only the new, not caring about the old anymore. Personally, I like to find products to care for, and in that sense, care plays a big role in my work.

How will it be used, how will it age and how could it become attractive for the user in all kinds of different ways?

AE: What critical questions should designers ask themselves when thinking about designing products and repairability?

JVDZ: They should ask themselves how they imagine a product-in-use—how will it be used, how will it age and how could it become attractive for the user in all kinds of different ways. It is not just about convenience but more about starting relationships. Many people talk about 'circularity' these days, but I feel like a product's life span should be stretched out as long as possible.

AE: Do you believe that makers, designers or manufacturers should be held accountable for their creations?

JVDZ: Yes, I do, especially big companies. When products are designed to break just after the guarantee period has expired—also referred to as planned obsolescence—one could argue that this is a criminal act. Many objects are designed as black boxes, and as consumers, we have no idea what is inside. Why not be more transparent about the products? We should challenge these producers to provide us with the information that we need to repair a product once we have purchased it. We should challenge them to make products easy, transparent and fun. We should also live with the idea that the products we create age and break eventually; it's a constant repair cycle we are part of. We just need to make the right choices.

planned obsolescence—one could argue that this is a criminal act

AE: How do you believe such a conversation with manufacturers could take shape?

JVDZ: There are several ways that manufacturers could make sure that the knowledge is available. They could collaborate with repair shops to receive feedback and make sure that the products are easily repairable whilst sharing their blueprints and instructions. Ideally, the parts required for repair should be produced by the company itself and should be made available to repairers as well. In general, people who repair products should be empowered and supported by the manufacturers. However, today our society is built around warranties and guarantees, in essence transforming products into legal time bombs or booby traps that no manufacturer wants to burn their hands on.

AE: How can manufacturers be motivated to become more transparent?

JVDZ: We could change our tax system. Taxes on resources could increase while taxes on labour could be lowered. This would result in a scarcity of materials which would automatically make us care more about them. This would motivate the manufacturer to get their materials returned to them or to be involved in a certain chain or cycle. Ultimately, this could also lead to a rethinking of the design and manufacturing process. Basically, a shift in value will have to occur.

I think the first step everybody can take is to open up broken products and try to understand how they work

AE: Do you have any advice for someone who is interested in repair and contributing to a positive change but doesn't know where to begin?

JVDZ: At a minimum, you can look at the repair cafés' websites and find out if there's one in your neighbourhood to assist you with the repair. But more generally, I think the first step everybody can take is to open up broken products and try to understand how they work. We should get interested in this process, seeing it as a journey to discover new knowledge. We should challenge ourselves to see a product as something that truly belongs to us and not as something that can be thrown away and replaced as soon as it does not function anymore. We have to try to connect with our products and go on an adventure with them.