Content type: Artwork, exhibition, interview

Credit: FRAUD, artistic research-duo of Audrey Samson and Francisco Gallardo. (Guest tutors, Graphic Design BA and Non Linear Narrative MA, KABK and speakers at KABK Research Symposium 2019).

Interview by Linda Kronman, originally published in Behind the Smart World: Saving Deleting and Resurfacing Data.

Year: The first edition of Goodnight Sweetheart: The Right to Happiness was made in 2015; however, new data-embalmings and exhibitions of the work are ongoing.

‘I was thinking recently about how it could be in the future, that you might have to pay to have things erased [...]So the rich people would be able to delete their data and the poor people would not.’

Introduction:

Destroying our digital data from our hard drives, phones, USB sticks, servers and social media platforms is both a ‘Sisyphean task’ and a ‘frightening prospect’, says Audrey Samson and Francisco Gallardo of the London-based artistic research duo, FRAUD. They consider that we live in a digital dilemma—on the one hand, we are never ready to part with our images but, on the other, in not doing so we submit these images to surveillance, consume energy with their storage and sharing and rely on companies and third parties to guard our private data, potentially risking losing it forever.

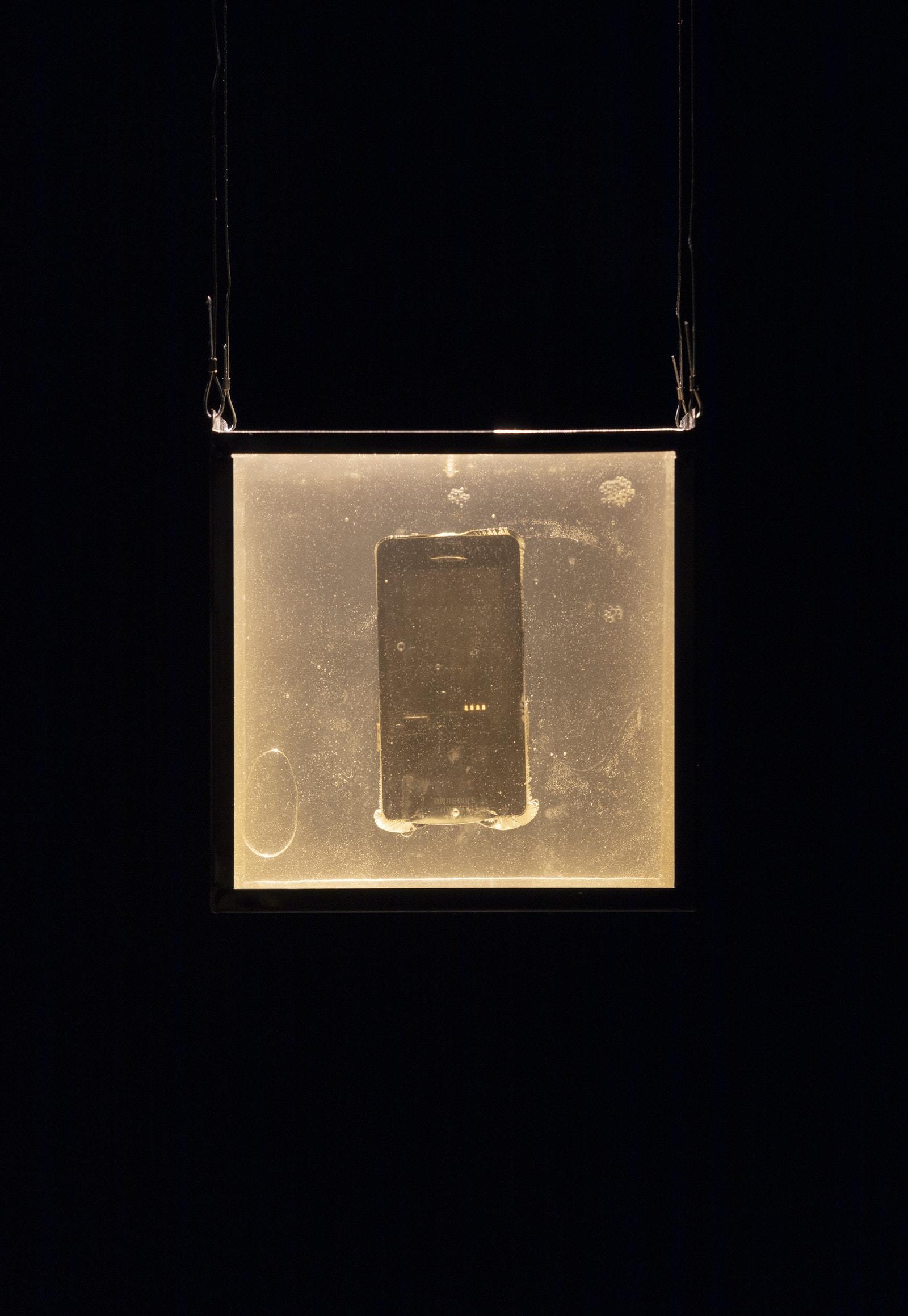

In the artwork Goodnight Sweetheart: The Right to Happiness, FRAUD performed digital data funerals—symbolic exorcisms for undead media—and then displayed the embalmed electric bodies in a museum-like installation. By collecting devices from others and embracing the seemingly absurd and futile act of embalming them, the artists wanted to reflect on the significance of rituals and the politics of deletion. When they exhibit the project, FRAUD performs digital embalmings on the audience's digital data and also hosts workshops on how to embalm your device. Ultimately, they ask: Who should choose what remains in "the cloud", online and in our devices? Do we have a right to delete, especially when this right is tied up with the ecological consequences of a growing digital pollution problem and the politics of power and money?

The following is an interview between Audrey Samson and Linda Kronman (media artist and designer) in which they discuss two of FRAUD's projects and their interest in digital detritus. It was originally published in the book Behind the Smart World: Saving, Deleting and Resurfacing Data, edited by Linda Kronman and Andrea Zingerle for the AMRO Research Lab, 2015. It is republished here under the ShareAlike 4.0 International Creative Commons licence.

The interview is interspersed with images from FRAUD’s most recent (at the time of writing) display of Goodnight Sweetheart: The Right to Happiness which was shown at the Fotomuseum, Switzerland from 24 October 2020 until 14 February 2021.

DIGITAL DATA FUNERALS

Linda Kronman: Your works ne.me.quitte(s).pas

Audrey Samson: Yes, both works are about erasing data, but as you say, it is rather impossible. In the works, the gesture is very symbolic. How difficult is it to erase data? I think it is nearly impossible, especially online. When one’s data is uploaded to the cloud, we normally don’t know where the server is, and the only real way to destroy data is by physically destroying the hardware by de-magnetising it or smashing it. Obviously, you can’t march over to Google somewhere in California and say–I would like to smash my section. And even if you could, because of how things are copied and propagated through the network, deleting data is practically impossible.

LK: Another thing you have written about is issues of data ownership after a person’s death. What are the current policies of the major social media platforms handling one’s digital legacy after death?

AS: These policies change very quickly so, hopefully, what I say is current, but it might be six months or a year old. For example, Facebook recently implemented the ‘Legacy Contact’, which is not available in all countries yet, but definitely in the US and DK. If you have Facebook, you may designate the person who would be your legacy contact in your profile settings. This person may update your profile picture, add new friends and download a copy of your Facebook data. You used to be able to choose whether your account should be deleted or memorialised (upon proof of death). But, of course, deleted is again a big word because they don’t really delete the data. Even if they delete your profile data, your ID still exists and all your data still exist, shared through other peoples profiles.

LK: What happens in practice when the profile does not appear anymore? Will the persons be deleted from the friend lists etc.?

AS: This is very recent, so there hasn’t been much testing on it. It should be that it takes you off all those lists. But when profiles have been "taken off" in the past, they still have appeared in, e.g., birthday reminders. Or they have this new thing called "your memories". This has been very troublesome for some people because, for example, their dead brother appears in ‘memories’ one morning. There is this kind of ghost in the machine that lingers on.

With Google, it is not really a death policy—they don’t even use the word death, which is very interesting. It is the ‘Inactive Account Manager’. We get this idea that we never die online; we just go inactive. The ‘Inactive Account Manager’ is not for death per se, but it deals with inactivity, for example, if you are in a state of health in which you can’t deal with your accounts. So, you are able to determine what you do with all your Google things, such as Google Wallet, Gmail, Google Drive, and all the other million things we have there. But if you say you want to delete something, you are not erased from the server logs. You are supposed to be able to erase your search history, but actually, you can’t because it is saved in the server logs. In that sense, your history is just somewhere else.

Twitter does not really deal with death (apparently, they would discontinue the account). Basically, if you are dead, how would they find it out and verify it? I am not sure how this works. There are so many services that will continue your Twitter presence even after you die, so the whole idea of death does not seem to exist on Twitter.

LK: That is also interesting: how does a company really know a person is dead? They might just be inactive.

AS: On Facebook, that was actually quite an issue. Because before the legacy contact, one had to show proof that a person is dead with, for example, a death certificate. But it appears that in practice, this was not always verified. It happened that someone said a person was dead, and it was a prank. The person’s Facebook was de-activated, but they were still alive. They then had to prove that they were still alive. So they got hacked in a way. This raises questions like: How do you prove that you are still alive when there are so many modes of presence through bots and algorithms? What does it mean to be alive anymore?

LK: So in the end, if we want to erase our presence from Facebook, dead or alive, it is impossible?

AS: I think so; nearly impossible.

LK: In your work ne.me.quitte(s).pas USB sticks with data are physically destroyed by using acid. And in Goodnight Sweetheart various storage mediums are embalmed in epoxy, totally blocking access to the data they contain. What was the process to choose these strategies of deletion for your artworks?

AS: I was thinking of ways to destroy data so that it could not be accessible anymore. Another more visceral way than just smashing the hard drive with a hammer. Then I met Jonathan Kemp, who was making gold cocktails from old hardware. You can strip the heavy metals by using a specific mix of acids called ‘aqua regia’ (HNO3+3 HCl). It is an old method to make gold soluble. I thought, wow, gold cocktails, this is such a poetic drink. Learning about the process of the acid being able to dissolve the metal, that’s when I thought–can we try this with the USB sticks? That is how the whole thing came about, through collaboration with him.

In the second iteration, it became apparent that using the acid as cremation of the data. I don’t know if you know someone who has been cremated? When you receive the ashes afterwards–it is a very strange material thing to receive. It became clear that the remnants I would send back in the post were like remnants from a cremation.

In the second project, I thought, what if we could embalm the data, make a relic out of it, in the way people embalm animals or humans at the funeral before burying them? The choice of the material came about for practical reasons; what can dry in such a way, in a certain time, that is transparent, and that can also have the embalming features. It ended up with resin for the devices and epoxy for the USB sticks.

LK: Both of your projects are also participatory. The data was chosen and given to you by the participants. Have you collected any statements of how they felt about the final erasure of the data?

AS: I have a little bit, and I must say that it is rather incidental in the sense that I never intended to ask people afterwards about the data. It was always supposed to be an anonymous thing. I never look at the data. I just either embalm or cremate it and send it back to them. Interestingly, I have been reproached for this. Apparently, it is my duty to collect metadata about what I erase; people cannot let go. But I did end up doing interviews about the project, incidentally with people that had done it, so I do have those statements. And interestingly enough, most of the people I spoke to had sent data relating to a past relationship. Not necessarily someone who died, usually a past boyfriend or girlfriend. So, for example, you have old pictures in your pictures folders and every time you go looking for an image, you might see an old photo of that boyfriend. These people would say that this gave them the opportunity to organise it in a way, to decide what to keep and what to delete, or just to erase everything, to get closure from that relationship. That was the story I encountered most often.

LK: The biological human memory needs to forget: How important do you think it is that in the digital realm, there is a right to be forgotten as well? On the other hand, when someone dies, we want to remember them by creating monuments; how does this translate to the digital?

AS: That is a tough question. I think it is very important to be able to forget. Both in the human brain, if we can make such a separation anymore, and online. To be able to erase is definitely crucial to the eventual function of our collective memory. But that is not to say – erase everything; rather – how do we then think about archiving in general? Archiving is always a power structure, so whoever gets to decide what we erase is also the one who has the power to decide such things. I was thinking recently about how it could be in the future that you might have to pay to have things erased. The people in control of the servers would have the ability to erase data, and it would be a very high-cost service. So the rich people would be able to delete their data, and the poor people would not.

LK: This is very interesting because today one is ready to pay for recovering lost data, so why not pay for deleting data? It sounds like a very evil business model!

AS: It does, but I think it is not such a far-fetched idea. It started a long time ago that when we get free services, all of what we do online is tracked. Even when we pay, it is tracked—all this information we give involuntarily to the company. Now there are services that will specifically ask you for more personal information, for example, tracking your heartbeat, and then you get the service for free. We are already starting to see the digital divide between people that have no money at all, that will just give away whatever information asked to obtain a service. I can see this building towards the point where there is all this evidence that can be used against you, as we know, and you should pay a big price to get it erased.

LK: As a last question, do you think there can be artistic strategies to deal with this?

AS: I think that artists working with strategies of deletion or erasure are addressing the issues. Thinking about networked data as part of ourselves, and therefore treating it in a different way, as a material thing with consequences, will help us to deal with these issues. Artists that work with the erasure of data emphasise the materiality of data, and this is very relevant. Demystifying the ephemeral cloud network fallacy will already change how we address these issues.